One week from today, Mormon women will attend the Priesthood Session of General Conference to show support for women’s ordination. Since January, Mormons have been studying Lorenzo Snow in Relief Society and Priesthood classes. Lorenzo Snow was educated at progressive Oberlin College, the first coeducational college in the United States of America and served as president of the church during the suffrage movement. The timing seems ideal to remember two suffragists who also attended Lorenzo Snow’s alma mater: Antoinette Brown and Lucy Stone.

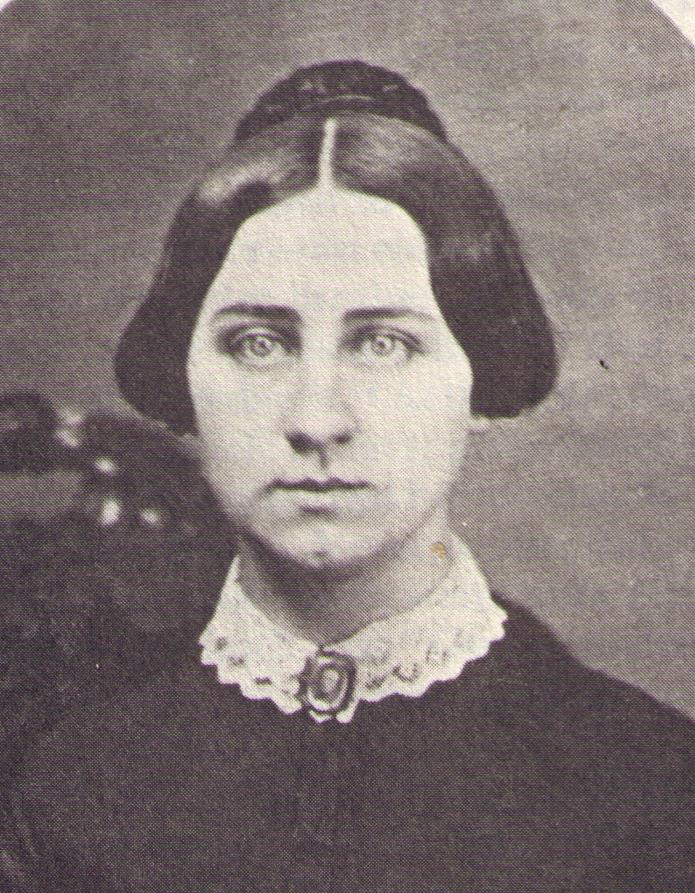

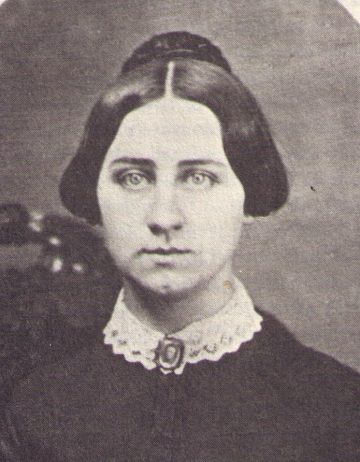

Lucy Stone sought to become a public speaker advocating for abolition and women’s rights, a scandalous plan at a time when the Biblical injunction to “let your women keep silence” (1 Cor. 14:34) was interpreted quite literally. Antoinette Brown’s plans were even more shocking; she wanted to become a minister, although no female had ever yet been ordained a Protestant minister.

Lucy Stone was raised by strict, traditional parents who believed educating a woman would be a waste of money. When Lucy learned that a new college was admitting women, she was determined to go in spite of the lack of support from her family. She saved for years to attend, finally obtaining enough money to enroll for one semester in 1843 at the age of 25.

At Oberlin, Lucy took several jobs with the hope of earning enough money to stay. During her first two years of college, Lucy slept little, awakening at 2 AM to study as her daytime hours were completely filled with coursework and the multiple jobs she was working to pay for her tuition and board. At her dishwashing job, she would prop her books up by the sink so she could study as she worked.

Oberlin was a station on the Underground Railroad and Lucy was offered a job teaching school to illiterate, escaped slaves. The male slaves protested her appointment. They felt it was beneath their dignity to be taught by a woman. However, Lucy quickly developed a rapport with her male students, such that several of them rushed to her aid during a dormitory fire.

During her third year, Lucy’s father realized that Lucy was working so hard that she was sacrificing her health. His heart softened and he offered to lend her the money to finish school on the condition that she pay it back promptly after graduation.

Although Oberlin was progressive for its time, it was not enough so for Lucy, whose views about abolition and women’s rights were even more radical. While Antoinette Brown was en route to Oberlin to begin her studies in 1846, a family friend warned her to stay away from Lucy Stone, who was “much too talkative on the subject if women’s rights.”

Antoinette later explained how this advice affected her:

Of course, she became the one person whose acquaintance I most desired to make.

Antoinette and Lucy enrolled in the same rhetoric course, where both were dismayed that women were expected to learn rhetoric by silently listening to their male classmates speak, in keeping with the prevailing taboo against female public speaking. When Lucy gave a speech at an anti-slavery community celebration, she was reprimanded by the Oberlin Ladies Board, a group of professors’ wives who governed female students. At one point, Antoinette and Lucy managed to convince their rhetoric professor to allow them to debate each other in class. By all accounts, the debate was “brilliant” but the event enraged other faculty and the Ladies Board. With rebellious snark, Antoinette reported that she actually enjoyed being called before the Ladies Board, as it gave her an opportunity to air her views, but their professor was forbidden from including women in debates again.

Lucy and Antoinette took matters into their own hands, organizing a “Ladies Literary Society” that met regularly to practice rhetoric. To prevent scholastic discipline, Society members met secretly far from campus at the home of the mother of one of Lucy’s escaped slave students. They were careful to arrive separately so as not to attract attention.

Lucy was one of several students chosen to “speak” at commencement, sort of. Oberlin asked female students to write speeches to be read aloud by a man on their behalf. Lucy unsuccessfully petitioned the faculty and the Ladies Board to allow her to give her own speech. When that failed, she declined the honor of writing a commencement speech.

After graduation, Antoinette applied to stay on at Oberlin for postgraduate theology studies. Unlike Lucy, she had enjoyed the support of her family as an undergraduate. That support evaporated when she announced her intentions to pursue the ministry.

Even Lucy thought Antoinette’s goal was outrageous. Lucy was confident that the church would never allow a woman to be ordained and wondered why Antoinette would even want to align herself with the church, which she saw as a corrupt institution that harmed women and punished free expression.

The Oberlin charter clearly allowed female participation in all courses of study but it had never occurred to Oberlin administrators that any woman would ever seek for the priesthood. Without statute to prevent her from enrolling, Oberlin officials reluctantly agreed to let Antoinette take the courses, but only as a “resident graduate” ineligible for a divinity degree.

Lucy was not impressed with this compromise:

Nette, I am sorry you are at Oberlin on terms which to me seem dishonorable. They trampled your womanhood and you did not spurn it. I do believe that even they would have thought better of you if you had stayed away.

Antoinette responded:

I came back to study theology and get knowledge. I do get it…I am not responsible for their conduct or their decisions…What if they or anybody else think I act unwisely, or dishonorably, or foolishly, what can that be to me?

While Antoinette found theological study at Oberlin spiritually fulfilling, it also had its challenges. The Ladies Board passed a new rule aimed at forcing Antoinette out of her paid Oberlin job. The assistant professor of the Ladies Department came to her aid and found Antoinette work as an independent art teacher.

Mentors were not forthcoming within the all-male ministry.

Associated as I have been this winter frequently with ministers, I have not found one that has been both ready and wiling to talk over the matter [of ordaining women] candidly…Some of them around here at least begin to feel a little uneasy in their old position and are not quite ready to advocate that.

In one class, Antoinette was given a unique assignment, different from that assigned all the male students. She was told to analyze the following scriptures, which were frequently cited as the reasons women were forbidden from priesthood (and even from speaking in public at all):

Let your women keep silence in the churches: for it is not permitted unto them to speak; but they are commanded to be under obedience, as also saith the law. And if they will learn any thing, let them ask their husbands at home: for it is a shame for women to speak in the church. 1 Corinthians 14:34-35

But I suffer not a woman to teach, nor to usurp authority over the man, but to be in silence. 1 Timothy 2:12

Antoinette recognized the assignment as a direct challenge to defend her priesthood goals and poured herself into study. Her finished essay argued that correctly translated and interpreted, Paul only meant only to guard against “excesses, irregularities and unwarrantable liberties.” Moreover:

The females were not forbidden to take part in the work of instructing the church, of speaking “either by revelation, or by knowledge, or by prophesying, or by doctrine” or of doing anything else which they had the wisdom and ability to do…and moreover…they did actually take part in these exercises.

Antoinette’s church had a nonhierarchical structure in which congregations could choose their own ministers. Three years after leaving Oberlin, in the spring of 1853, Antoinette found a congregation willing to hire her, in part because they could not find a male minister willing to accept their low wages. Antoinette was ordained that fall. However, after only a year of work, she felt compelled to resign due to a crisis of faith. She turned her attention to writing books and freelance preaching. In 1878, she decided to pursue the priesthood again within a different Protestant denomination. Meanwhile, Oberlin finally deigned to give her an “honorary” theology degree for the coursework she had actually completed. She was unable to find a congregation willing to hire her at that time but she continued lecturing and eventually did have the opportunity to work as a full-time minister again in her elder years.

Lucy Stone was able to pay back her father and earn a comfortable living off of speaking fees for her speeches on women’s rights and abolition. She was the first woman to speak on the Massachusetts Senate floor, organized the first National Women’s Rights Convention and founded the American Woman Suffrage Association.

One of Lucy’s greatest speeches was delivered extemporaneously in response to a heckler who dismissed the women’s rights movement as the work of “a few disappointed women.” Her response is still hauntingly relevant to modern feminists, who often find that defenders of patriarchy are other women who don’t “feel” unequal:

In education, in marriage, in religion, in everything, disappointment is the lot of woman. It shall be the business of my life to deepen that disappointment in every woman’s heart until she bows down to it no longer.

The two best friends became sisters-in-law when Lucy married Henry Blackwell and Antoinette married Samuel Blackwell, the two brothers of Elizabeth Blackwell, the first American woman to get a medical degree. Lucy and Antoinette never did share a surname, however. Lucy Stone was the first known American woman to keep her name after marriage.

Bibliography

Blackwell, A.S. Lucy Stone: Pioneer of Women’s Rights. Little, Brown and Company: 1930.

Cazden, E. Antoinette Brown Blackwell: A Biography. The Feminist Press: 1983.

Kerr, A.M. Lucy Stone: Speaking Out for Equality. Rugers University Press: 1992.

Laser, C. & Merrill, M.D. Friends and Sisters: Letters Between Lucy Stone and Antoinette Brown Blackwell. University of Illinois: 1987.

Hays, E.R. Morning Star: A Biography of Lucy Stone 1818-1893. Harcourt, Brace & World:1961.

3 Responses

Wow, this is amazing, April! I have read Antoinette’s autobiography, but I have never read anything about Lucy Stone before. I love many things about their story and their friendship, but one of the things that jumps out to me the most is how they were transgressing racial divisions as well as gender divisions. I love that they met at the mother of an escaped slave student’s house and that Lucy developed great relationships with her African American students. Thanks so much for posting this, April. What a great window into these amazing women’s lives.

This is fantastic! Thank you for taking time to compose this. Just a few hours ago I was thinking, “I need to read more about women’s and feminist history.” How about that, April? This post is an answer to my prayer! And you’re right, it’s a good time to re-visit stories about the lives and contributions of women like these two. Loved it.

Such fascinating (and relevant) history. Thank you for sharing your research in such a poignant manner.