by MargaretOH

Everyone has multiple identities. For the most part identities are either peacefully nested (i.e. a Mid-Westener and an American) or separated (i.e. lawyer and PTA member). Sometimes self-identities will come into conflict, as might happen for a homosexual Mormon. Collective identities coming into competition or conflict may explode as violence or civil war. “To understand how struggles erupt, then escalate, de-escalate, and become resolved, we must recognize that identities change in content and shift in salience” (Kriesberg 55). Post WW2, a strong Yugoslav identity, rooted in pride at having resisted the USSR, held the country together for several decades. Ultimately, the primary identities shifted toward Serbs, Croats, Slovenes, Muslims, and Bosnians, with tragically violent results. How the Yugoslavs saw themselves individually changed the collective narrative dramatically, creating competition among identities and escalating conflict.

My own feminist and Mormon identities have pushed and pulled against and with each other. Sometimes they feel nested, comfortably fitting as a group and sub-group. At times they feel completely separated, although this is increasingly rare for me. Sometimes they feel like they are in competition and like I will have to choose sides in a civil war. Those days are difficult. At those times I consider how identity can build or destroy communities and I have to make a decision whether my own internal conflict will be productive or violent.

Four interrelated internal characteristics determine the strength of a group identity. They are the homogeneity of members, ease of communication among members, clear boundaries of the population, and potential and ability to organize. These four factors will help determine whether a group sees itself as having a shared identity and common interests and whether they believe they have a grievance has the potential to be remedied (Kriesberg 56).

“In defining themselves, groups also define others; and in defining their opponents, they also define themselves. Each self-conscious collectivity defines non-members; indeed, identity is in good measure established in contrast to others” (Kriesberg 60). If we know who we are by whom we are not, then Mormon feminists run the risk of seeing themselves as separate from the general Church body. Mormon feminists have high levels of homogeneity (we are, after all, talking about a small sub-group of a small religion), easy communication through the internet, a bounded population group, and an increasingly strong ability to organize. While the community has been a lifeline for many of us (myself included), it is easy to tip that scale towards exclusivity and drawing lines between people.

Activists are even more inclined toward an intense identity affiliation because of the sacrifices they’ve made for their cause. The more a person puts resources into a cause, the less willing they are to walk away from it. An easy example of this is being put on hold: the longer you wait, the harder it is to hang up and lose that wasted time. The LDS Church requires a great deal of sacrifice from its members; members are correspondingly devoted and protective. Once activists have made a sacrifice for an issue, it is much more difficult to step away, even just far enough to see from a different perspective or to reconsider the rightness of the cause. Self-defense becomes standard behavior.

“People are generally inclined to evaluate their own group as superior to others. This universal tendency toward ethnocentrism contributes to the sense of each group to view relations with other as one of “us” against “them” (Kriesberg 61). Ordain Women, Exponent II, and other Mormon feminist groups have been careful to officially place their identities as nested within the LDS identity. Exponent II speaks to the variety of lived realities for Mormon women. OW’s founder Kate Kelly says, “We are not against the Church; we are the Church.” Yet in more informal, homogenous gatherings in person or on blogs, I hear and read statements that veer close to Kriesberg’s warning. Certainly I have heard orthodox Mormon women state that they feel like OW has treated them as inferior or unenlightened. This is worrisome to me.

What can be done about an escalation of conflict due to identities in competition? I have two suggestions:

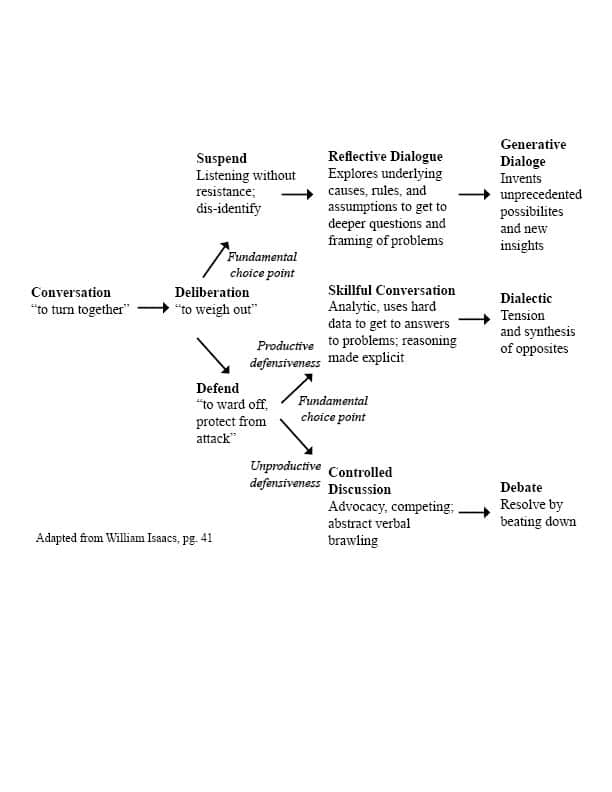

1. Move the conversation from defending to suspending to dialogue. In the public forums (which are, not by coincidence, horrible platforms for dialogue), I find condescension, defensiveness, argument, and bullying to be the norm. Occasionally someone asks for genuine understanding and their partner in conflict happily supplies them with an explanation. I have never seen the responder then ask, in their turn, for understanding. These “conversations” are not about listening or about valuing relationships. The diagram below illustrates the choices we can make when listening and speaking and the consequences of what will emerge:

(The image of the chart here is a bit fuzzy. Go here for a clearer version. conversation flow chart)

I believe that activists making a sustained effort toward deliberation and suspension and refusing to engage with those who simply want debate, could revolutionize the framework of the conflict.

2. In conflicts where one party is much more powerful than the other, there is a balance between encouraging empowerment of the less-powerful group and building trust between the groups. This often seems like a difficult line to walk, as the more-powerful group may become more defensive and less trusting as the less-powerful group gathers strength and voice. I will speak more to this is the next blog post of this series. However, healthy empowerment of the self and a stronger partner in conflict are paradoxically intimately connected when viewed through the lens of building community. Conflicts can change enormously simply by understanding that “empowerment involves mutual dependence. ‘I can’ is only fully accomplished with ‘I need you’” (Lederach 21).

I have seen both Church leadership and feminist activists send the message of “We love you.” I have also heard people feel empowered enough to state, “I can.” “I need you” goes a step farther in exposing vulnerability. It also breaks down the identity barriers we may have constructed between “us” and “them”. While with some conflicts we pray merely for the negative peace of a ceasefire, we hope that conflicts involving important relationships are more productive: that they actually bring people closer together through the process of solving them.

Resolutionaries can find a calling in moving the conversation towards dialogue and preserving mutuality and community. “To listen respectfully to others, to cultivate and speak your own voice, to suspend your opinions of others—these bring out the intelligence that lives at the very center of ourselves—the intelligence that exists when we are alert to possibilities around us and thinking freshly” (Isaacs 47).

Works Cited:

Kriesberg, Louis. Constructive Conflicts: From Escalation to Resolution. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2007. Print.

Isaacs, William. Dialogue and the Art of Thinking Together. New York: Currency, 1999. Print.

Lederach, John Paul. Preparing for Peace: Conflict Transformation Across Cultures. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University, 1995. Print.

18 Responses

What a great post, Margaret. So much to think about!

I am very interested in the idea of moving from defending to suspending to dialogue. My question is how do Mormon feminists do this when institutional church leaders won’t be dialogue partners with us. I have no doubt that a bunch of Mofems could sit down with the 12 and have a wonderful, vulnerable, open, and loving discussion about Mofem concerns…. but that’s just not a possibility. And that’s the audience we need to reach if we want to see any real changes in the church. Do you see the next best thing as dialogue with everyday Mormons? Maybe local Mormon leaders?

Caroline, you’ve articulated my feelings here. I believe in the power of listening, and in forbearance, but I’m not sure how much more of those things I can do; I feel like vis-a-vis the institutional Church, that’s all I do.

Margaret, your post has made me think about things I haven’t considered before, so thank you for that – I’m really looking forward to your next piece!

Caroline, This is quite true. I had the opportunity to talk with Elder Niel Andersen of the Twelve a few years ago when he came to our area. He wanted to talk to my husband about his book, but when I requested to be at the meeting also, as president of Exponent II, he readily agreed. We talked openly about various issues and he was quite receptive. However, I knew that our conversation was just that– a conversation– not a beginning, open dialogue.

The problem with trying to work with local leaders is that it is painfully slow and usually what gains we make never make it up the food chain. For example: I have worked with my bishop to include the YW in helping with the sacrament. The YW will be the ones who will check the mothers’ lounge to see if any of the women are in there nursing and need to take the sacrament. The deacons will hand the tray to the YW and she will take it in the lounge to the mother. I had to explain to the ward council that this is no different than me passing the tray to the person next to me and that it doesn’t “interfere” with any priesthood duties. No one seemed bothered by it and agreed to the proposal. This was done on a ward level– will it make it up to the Stake? The area? The Church as a whole? Probably not. I have learned over the years to work with the small steps and try to be content that I can help make a difference, even if it is only local and may not last. (The Stake has yet to discover our “plan”…)

This is really helpful as I think about the interactions I have on Facebook. I’m usually inclined to activism by example (is that a thing?). I rarely engage in debate and when I do, I’m usually directing my arguments towards the people who are silently reading and thinking.

The idea of expressing the need of the other side’s view and acceptance of that opinion during debate is a radical (and scary!) one to me. I often think it–I do appreciate seeing the other side because it helps me from snowballing in my ideas, but it’s hard for me to imagine expressing that sentiment during a debate. I’d almost feel like I was conceding defeat.

Can’t wait for the next post, my friend!

Emily, I think you’re right that admitting the validity of a conflicting perspective is one of the hardest things for us to do. I’m grateful for the measured and charitable voice that you’ve added to conversations. You’re a great example for all of us.

I was part of a mediation team that was working on informal talks between Israelis and Palestinians. The frustrating thing about that conflict is that everyone already knows what a peace agreement would look like. All the big issues have been addressed many times and maps have been drawn out dividing the land and everyone really involved knows approximately what a final peace document will look like. So all the bureaucratic, technical, wonky stuff has been done, it’s just we can’t get people to admit to the hurt they’ve caused and the wrong they’ve done. You get people in a room (and these are people who are willing to try!) and they just keep stating over and over again how they are right and how they’ve done less harm than the other side.

I remember one specific example of a Palestinian (who had been part of the Clinton peace talks at Camp David) and an Israeli (who was part of a pro-peace group in Israel) arguing about how serious a certain battle had been. The Palestinian was shouting about how the death toll hadn’t been very high and how the Israelis had overemphasized this battle because they could look like victims, etc. The Israeli suddenly got quiet and said, “The death toll was high enough. My wife’s father died there.” Everyone quieted. Almost everyone there could have matched that statement with their own claim to grief or loss and I worried that we were going to veer back into a conversation of competition. Instead, the Palestinian who had been yelling said, “I’m sorry, [first name].”

It’s a dramatic story and I don’t mean to imply that the conflicts are particularly comparable. However, it does illustrate how difficult it is to acknowledge the other, even when a framework for peace is tantalizingly close. In the case of the Church-MoFem conflict, it’s still very unclear what kind of future could be acceptable to both parties. That’s going to make vulnerability and mutuality, with their potential for losing face, quite difficult to attempt. It’s worth remembering that, like the Israeli who held his father-in-law’s memory in his heart as he worked, just about everyone who speaks up in this conversation is going to have personal experiences that guide them there. We can at least validate the experiences even if we’re not ready to accept the opinions.

This is a great post on an important topic. Without suspension and dialogue, defining lines can be drawn even among feminists: “what kind” of feminist are you? What positions do you espouse? The divisions can seem even deeper between those who identify as feminists and those who don’t. This analytical framework you’ve outlined explains so lucidly why we feel passionately, and often passionately defensive, about the causes for which we have sacrificed and which form a part of our identities. I love how a recognition of mutuality and vulnerability–that different identities/divisions within a community each make important sacrifices, and that the community as a whole needs and benefits from all of these–can strengthen community and smooth divisional lines.

Thanks for making me put on my thinking cap this afternoon! You’ve given me a lot to process. I can’t wait to read more.

Another excellent, thought-provoking post, Margaret. I think the “Mormon persecution complex” plays an interesting role in all of this–as an institution we’re very good and ingraining a narrative that plays up an “us against the world” mentality. It’s not surprising to me that a Mormon feminist subculture within the larger Mormon culture may experience double that sense of outsider-ness as they face both suspicion from without (non-Mormons) as well as within (Mormons who consider feminism an evil of “the world”) .

And yet I can’t help being struck by what Caroline noted–that the group wielding institutional power is unwilling to engage. What seems more defensive–the asking for dialogue or refusal to engage?

Great post.

Although it’s hard for me to admit, I know I’m guilty of drawing the line between us vs them. My husband has also mentioned the idea to me that he sees Mormon Feminism as a community/cause I’m invested in and therefore cannot separate from, even if I disagreed. I’m not sure how I will use this new type of information going forward, but at the very least, you’ve reminded me to do more than just try to play nice. I really need to try to listen.

Why is it so much easier to notice when other people aren’t listening? My husband is slightly more liberal than me on economic issues. I see him as being partisan but he vigorously denies it. But then, I’m more liberal on social issues and when he presents a more moderate perspective I have to work hard to suspend judgment. Thanks for your thoughts.

Thank you for this thoughtful post. It raise more questions for me. For one, I am curious how you see the Mormon feminist population as “bounded.” I see it as highly fluid, with people coming in and going out at rapid rates. I see the church as more bounded, because it has formal membership. Am I missing something?

How would you recommend that OW supporters prevent traditional women from feeling like they are being treated as inferior? Do you have any tips?

April, thanks for the questions. Re: the bounded populations, I would agree with you that this is the descriptor that least well applies to the Mormon feminist community. Perhaps I am speaking just from my experience in an inner-city ward, but I also see the LDS Church as bounded but fluid, with people moving in and out of activity and with a wide spectrum of commitment. The population gets more bounded on both sides when you move to the people who are actively engaging in the conflict. While the bloggernacle is a loose collection of people who wander in and out, the people with profiles on OW or people whose names are on the staff of Exponent II are highly bounded. They have publicly stated who is in (and, by default, who is out).

The second question is more difficult. For research purposes for a separate article, I’ve spent a fair amount of time on the OW Facebook page reading through comments. There’s clearly a gap in the level of courtesy and compassion between supporters and detractors (with supporters winning the prize for basic manners). And yet I keep hearing from women who say that they feel put down and unheard.

I suspect that the negative messages these women are experiencing are much more covert than the angry diatribes on FB. For example, I hear OW supporters saying over and over again that equality is not a feeling. It’s a clever response to women who say that they feel equal, but frankly, it’s not a bridge-building one. It’s a response that has the implied message of, “No, you’re wrong. You just don’t see clearly. Your feelings are not as valid as my measurements. Your perspective is not worth listening to.” I don’t believe that’s the intended message but I think that’s the one other women are hearing. It’s a response that shuts down dialogue. I believe that a very different message would come from someone saying, “I hear you saying you feel empowered and important in the Church. Tell me more about that.”

You’ve been more involved in the OW conversations than I have. I’m sure you’ve heard from women who feel hurt. What do you hear from them?

Actually, while I have heard from several people who disapprove of me for supporting Ordain Women, I have only heard from one person who has told me that she finds my comments in support of the ordination of women to be offensive to her and to women generally, and I am at a loss to understand what she is referring to. But I can see what you are saying about “equality is not a feeling.” I don’t think that I have personally used that slogan, but when I receive a question like, “What is wrong with you? Do you have rotten priesthood leaders and a horrible husband? Are you just trying to be offended? My priesthood leaders and husband are great and I don’t get offended by silly things and I don’t feel unequal.” I tend to respond by pointing out measurable, systemic inequities that concern me, and I guess this is a long version of “equality is not a feeling.”

That’s not quite what I meant. When you respond with your own experiences and views, that’s healthy and good. In a dialogue, this should lead to greater understanding. What I’m referring to is when feminists say, “I’ve had women tell me that they feel equal in this Church. But equality is not a feeling.” I’m not sure who started this line but I’ve heard it requoted again and again. It is not speaking from a personal perspective, but rather insisting that those women are wrong and that their feelings are incorrect. Instead of trying to understand them, it is increasing the dividing lines between enlightened “us” and ignorant “them”.

I don’t want to get bogged down in a single example but I think this is a useful one for seeing how hurtful communication and shutting down dialogue can happen unintentionally, not just from yelling ridiculous accusations on Facebook.

I’m also surprised that you haven’t heard from women who have felt hurt by OW. There was someone who spoke up in the comments from my last post and in my personal interactions, I’ve heard it several times. I haven’t done enough exploring in those conversations to know for sure what’s going on there, but it’s definitely worth trying to understand.

Thanks for the comments, everyone. This is a busy weekend for me (come to the Speaker Series event with Claudia Bushman tonight!) so I may be slow in responding to comments. I promise I’ll address how to engage in dialogue with an unwilling partner soon.

Thanks for this. And especially this:

“. . . identity can build or destroy communities and I have to make a decision whether my own internal conflict will be productive or violent.”

To be honest, I’m a bit of a scrapper. I don’t mind taking a fight out onto the streets, but I’ve learned it’s exhausting and ultimately unproductive. So, I rarely engage in discussions on facebook. And I tend to “drop and run” with blog comments, because I don’t have time to engage in electronic discussions there either. But this makes me wonder if my comments are more useful to myself than anyone else. Especially in revealing my own biases.

Anyway, I love this post. I love the science behind it and the potential for healing and for mutual understanding when we pay attention to such things. Thanks again.

I’m going out on a limb here in response to Margaret and April’s thread above . . . so I ask for a willingness by readers to be objective. This is my experience and my perception. But I think it is worth mentioning.

I have seen and heard some Mormon feminists and members of OW use language and non-verbal behaviors, such as: facial expression, voice tone, etc. that communicate a sense of superiority toward other women. I see this often. I’m not alone either. A few of my Mormon feminist friends and I have talked about this.

There is no way to know how this superiority is communicated individually, but globally, it seems to have a flavor of academia and professional achievement linked to it.

Please, do not shoot me. I am only the messenger here. There seems to be a feeling expressed by this particular variety of MoFem, that if other women would educate themselves about feminist theory and cultural sexism, or if they would step outside their limited world view (and their conservative Mormon lifestyle) they would see what certain other of their feminist sisters see. Then they would understand OW and like-minded others.

The scripture in 2 Nephi makes great fodder for those who want to diminish the valid points of the well-educated, professionally accomplished feminists among us. (Some women tend to metaphorically use their CV to shore up their position.) “When they are learned they think they are wise, and they hearken not unto the counsel of God, for they set it aside, supposing they know of themselves . . .”

So, my suggestion is: if you are one of these people, if you are well-educated and professional, ask yourself if you in some ways FEEL superior to your less-educated and non-professional sisters? If you don’t feel superior, then this comment doesn’t apply to you. If you do find yourself in such a position, consider the possibility that you are unintentionally communicating things that separate you from some of your sisters in the gospel.

Thanks for bravely sharing your experiences, Melody. At the Exponent II Speaker Series event on Saturday, Claudia Bushman was encouraging every woman to do art and every woman to write. She said that keeping a journal is good for us because it helps us honestly examine our lives and that an examined life is richer and fuller. I think we can all live with more self-examination and deliberate compassion.