by Lucy M. Hewlings,

by Lucy M. Hewlings,

First published in The Women’s Exponent, vol. 7 no. 17

February 1, 1879

The question has been asked, “Was there ever a time when there were no learned women?” To this query we reply, No! never since the creation of Eve, our first mother, down to the present, when the cause of women’s social and political rights has become a distinct national question; we admit there has been an unusual intellectual activity for the last twenty years, both in Europe and America, and that there has been advancement and progress in this respect within the last decade, but we are apt to felicitate ourselves, and perhaps are too indiscriminate on the progress achieved in female education.

There never was a time, let me repeat, when there was not highly educated women, according to the standard of their age. Isis and Minerva show the value set upon feminine intellect by the ancients. Recall the noble tribute of Pluto to the genius of women in his Banquet; also the long line of learned and accomplished English women, from Lady Jane Grey to Elizabeth Barrett. Among that wonderful people, the Spanish Arabs, there were women who were public lecturers, secretaries of kings. While Christian Europe was sunk in darkness, Ayesha, daughter of Ahmed ben Mahommed ben Kadin of Cordova, was considered the most learned woman of her age (the Tenth century); she excelled in mathematics, medicine, poetry, and other sciences. The Moorish historian almost deifies this then wonderful woan. There were female professors of the classics, and of rhetoric at Salomanca and Aleula under Ferdinand and Isabella. The intellectual influence of Lucrezia Borgia is classed by Roscoe with that of his hero, Leo X. Vittoria Culonna and Veronica Gambava ranked as the equals and friends of Bembo and Michael Angelo; Tisaboschi declared the Rimatrice, or female poets of the 15th century, not inferior in number or merit to the Rimatori, or male poets. Benedict XIV bestowed on Maria Aynezi, a celebrated mathematician, the place of Apostolic professor in the Univeristy of Bologna in 1758. Pope Clement XIV wrote, in 1763, to a lady who had sent him her translation of Locke, expressing his satisfaction that the succession of learned women was still maintained in Italy. There is a work of Paul de Ribero, entitled “The Immortal Triumphs and Heroic Enterprises of 845 Women.” There were sold at Padua in 1847, from the library of Count Leopold Terri, 30,000 volumes soley the works of female authors. Donna Maria of Portugal, who married Prince Alexander, grandson of Charles V, could talk in both Latin and Greek; she was said to be well versed in philosophy, mathematics and theology. Madame Roland was acknowledged a far better Statesman than her husband. One of the most important treaties of modern Europe, the peace of Cambray in 1529, was negotiated by two women, Margaret, the aunt of Charles V, and Louisa, the mother of Francis I.

These are merely a few specimens given out of thousands. There always have been strong-minded, energetic, brilliant women, but in order to succeed there must be an incentive to action, and all acquired faculties are to be brought to bear upon some definite end. Indolent young men have been galvanized into industry when the final pressure on an immediate aim was supplied. A few, both male and female, have so strong a propensity for study that they pursue it by themselves, though without any ulterior aim. But for most of those of average energy there must be an object for the employment of their time. The end and aim in the schooling of our girls has been to fit them to be wives and mothers. This must never be lost sight of. But our boys have the probable destiny of becoming fathers and supervisors of the intellectual training of their children. Our boys have this sacred responsibility to arouse them, and al the incentives of private and public duties.

What is it that so often causes failure on the part of girls, when it has been proven that at school the girls showed more aptitude, and averaged an equality of talent. Let me give the answer as it has come up from thousands of female hears: “We have nothing to do.” Boys go to college, study professions, learn trades, etc., etc. They have all before them, while most of the girls feel that they have nothing worthy to inspire them, and the failure arises from want of stimulus. An immortal soul needs for its sustenance something more than visiting, novel reading, crocheting, making pretty little things to adorn person or parlor. This is not sufficient- neither is that other incentive so often held forth to young women, viz., “To be the mother of some great man like a Washington or a Marshall.” This has been the burden of address in school examinations by the learned (or otherwise) gentlemen present. This they seemed to think was sufficient to inspire heart and mind forever! To be the mother of a sublime specimen of male humanity! Some critic, after speaking very cordially of Mrs. Mill’s able article, “The Enfranchisement of Women,” in the Westminster Review, said that it was to be hoped, however, the mother of J. S. Mill would always regard it as her chief honor to have reared her distinguished son. But why is it not as much honor to be a useful woman as to be a useful man? Must this be the great ultimatum of woman’s life here- to be spoken of after a generation or two, or more, as the mother of the learned renowned, famous James, Charles, or John So and so? We believe most women prefer to take the honor as they go along; not that any woman would object to being the mother of a good son or daughter- we consider it an honor to have either. The father may be as important in the rearing of the child as the mother, yet it is not considered the whole duty of man to be a good father. Many men who have been good fathers have also attended to the arduous duties were, in fact, many of them, guardians of American libery. And has woman only one-half a mission? Is not each individual, male or female, an unit before God? Has woman equally with man an individual body to be protected, and an individual soul to save? Must she not see, feel, know, speak, think, act for herself and not through another? Is not the same grand universe, with all its wonders and mystery, spread out before her for study and research? Are not the same deep thirstings for knowledge within her soul? Has she not the same solemn and profound problems to solve that man has? And can she not attain to as great a scientific or literary eminence as her brother man? Is she not a mental, moral, spiritual being, and as such, accountable to her Creator, who has placed her here by the side of man under the same obligations to develop and unfold her God-given powers? It is arrogant and audacious presumption for man to attempt to decide the sphere of woman, especially in an age that can number its thousands of noble, intellectual, earnest workers for the right, each one of which has mind enough to set up half a dozen like many who disparage woman’s capacity.

Woman asks the same intellectual and political advantages that are granted to man. All women have the natural right to labor, suffer and endure- no one attempts to deny this: but she asks the same encouragement to give energy to industrial enterprise. Says an American writer: “Tho dignity of labor should be sustained. The franchise of a freeman should be granted to the humblest laborer who has not forfeited his right by crime. In the responsibilities of a freeman he will find the strongest motives to exertion. Besides, so far as government can by its action affect his confidence of a just remuneration for his toil, he feels that a remedy is put in his hands by the ballot box.” Some of our law makers have asserted that the right of suffrage was worth fifty cents a day in effect upon the wages of the male laborers in this country. The great educator of American men is the ballot box with its accompaniments, and this means the whole world of public life, public measure, public interests and public offices.

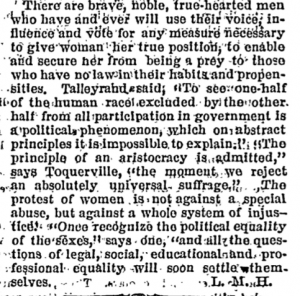

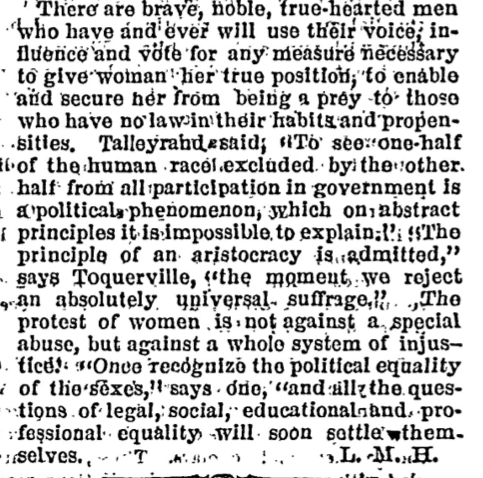

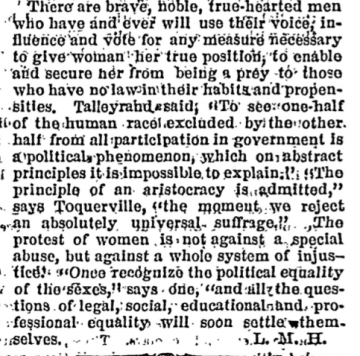

There are brave, noble, true-hearted men who have and ever will use their voice, influence and vote for any measure necessary to give woman her true position, to enable and secure her from being a prey to those who have no law in their habits and propensities. Talleyrand said, “To see one half of the human race excluded by the other half from all participation in government is a political phenomenon, which on abstract principles it is impossible to explain.” “The principle of an aristocracy is admitted,” says Toquerville, “the moment we reject and absolutely universal suffrage.” The protest of women is not against a special abuse, but against a whole system of injustice. “Once recognize the political equality of the sexes,” says one, “and all the questions of legal, social, educational and professional equality will soon settle themselves.”

L. M. H.

5 Responses

This was absolutely fabulous.

This: “The father may be as important in the rearing of the child as the mother, yet it is not considered the whole duty of man to be a good father. Many men who have been good fathers have also attended to… arduous duties…. And has woman only one-half a mission?”

Thank you for re-posting this great gem.

Thank you for sharing this eloquent article!

This is powerful and (apparently) timeless. I’m amazed at the strength and insight of our foremothers. I’m a little saddened by the ongoing challenges we face as women. Hopeful, but also saddened. Women have been singing the same song for centuries. When will we have cause to sing a loud and lasting “Hallelujah!”?

Sometimes when I read Woman’s Exponent, I get so excited to see such eloquence on these themes from the 19th century. And other times, I think, “Shoot! These arguments have been made for 175 years and this is as far as we’ve gotten?”