Guest post by Heidi Toth, who lives, works, writes and runs in Flagstaff, Arizona, with her dog. She is earning a degree in religious studies from Arizona State University, writes midrash about the Hebrew Bible, and is an introvert in an extroverted church.

For many years, I have sought out the voices of women in the scriptures—learning their stories and understanding their critical roles in God’s plan. I have wept with Hagar as she cried for her son in the desert and spoke to God; gone to battle with the prophet Deborah (Judges 4); faced scorn with grace and courage alongside Queen Vashti (Esther 1:11-22); and grasped at the hem of the Savior’s robe, trembling with hope and fear alongside the unnamed woman who suffered from a chronic illness (Luke 8:43-48).

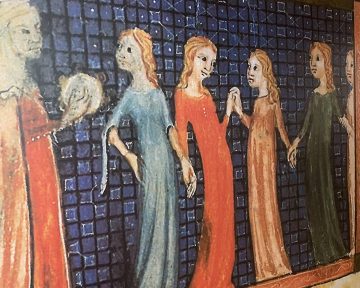

As I walked with these women, they led me to the feet of the Savior. The women of the Bible often come to know Jesus in quiet, humble ways—on their knees; seeking guidance and forgiveness; crying out in the darkness; serving others; and speaking up for what is right. Four women play an especial role in the Savior’s mission on Earth. They share a love and intimate knowledge of Jesus Christ. They also share a name.

Mary of Nazareth, mother of Jesus, the first mortal witness

When she was young, an angel came to Mary and asked her a question that no one before or since has been asked—would she bear and raise the Son of God? The author of the Gospel of Luke tells us Mary was troubled when she saw the angel, that she asked questions, that the angel spoke to her as a competent, capable woman, and that she had faith to say yes. But what else went through her mind? Did she ask, “Why me?” Did she know what the Son of God was being sent to Earth to do? Did she talk to anyone before she made her choice? What did she tell her parents? Did they believe her? We know she sought out Elisabeth, her cousin, and these women became the first people to bear testimony of the Savior’s divine mission (Luke 1:26-55).

Nine months pass. Imagine the joy and love in that tired little mother’s eyes as she studied her newborn son. Did he have her ears or eyes or chin? For most of his life, Jesus belonged to his Heavenly Father, but I think in those early moments, the son belonged to his mother. She was the first person on this Earth to know him, to know his eternal identity. On Earth, she knew who Jesus was before he did.

The scriptures tell us of a number of interactions between Mary and Jesus. When he was 12, she and Joseph had to go back to Jerusalem when they discovered he was missing from the caravan, only to find him teaching in the temple. She gently rebuked him for causing them worry. He gently rebuked her for forgetting his higher purpose (Luke 2:42-52). Their relationship shifts as he comes to understand his mission, but there is no sign of her testimony in him or love for him faltering. When she tells him of the lack of wine at the family wedding in Cana, she has no doubt of his ability to do the impossible. He rewards that mother-love and faith with the first miracle of his ministry (John 2:1-11). Her faith stands as a witness, inviting others to behold Jesus as she had that night when she held him in her arms for the first time.

Mary of Bethany

The second is Mary of Bethany, a close friend of Jesus. In Luke 10, we read of Jesus coming to the home of Mary and her sister, Martha. Martha showed her love by cooking and cleaning and preparing the house. Mary showed hers by sitting with the Savior and listening to his words. I think she contributed, that she asked questions—but mostly, she listened. When the Savior of the world is in your living room, you listen.

I can’t come down too hard on Martha. Hers may not have been “the good part,” but the mundanities of normal life matter too. Somebody has to make dinner, wash dishes, meet the deadline, finish the paperwork, fix the flat tire. It’s impossible to truly shut off our inner Martha—and really, we shouldn’t. I mean, if the Savior comes, forget the dishes and listen to him. Until then, do the chores. But in this instance, heed Mary. She sensed the eternal nature of the Savior’s mission and recognized the importance of learning from him and putting that above traditional domesticity, which didn’t happen among women in Jerusalem in 30 CE.

We meet Mary and Martha again, entwined in heart-wrenching sorrow. They sent for Jesus when their brother, Lazarus, fell ill. Jesus did not come. Lazarus died. The author of the Gospel of John tells us Jesus loved these siblings, yet he did not come when sought. When he did arrive, four days after Lazarus’ death, he is met by a grieving but not reproachful Martha, who testifies that she knows Jesus could have saved her brother and then testifies that she knows Lazarus will be resurrected (John 11:1-27). She has a powerful motivating faith in Jesus and understands the purpose of his mission, if not what he intends to do here.

Mary follows a similar path. When she knows Jesus is coming, she goes to meet him. She falls at his feet, weeping, and utters a sentence that is equal parts faithful and heartbreaking: “Lord, if thou hadst been here, my brother had not died” (John 11:28-35).

This is not an accusation. Mary is not demanding to know why he didn’t come. She is expressing great pain and great faith in Jesus’ power as she understood it. She is not saying Lazarus, or she and Martha, deserve a miracle, but she is laying claim to their right as believers to seek miracles. I wonder—do each of you feel you have that right? I have never, in all my years getting to know Jesus, felt I had the right to a miracle. Each time I asked, I have done so as if asking for a favor. Mary’s is a statement of fact: Had Jesus been there, he would have healed Lazarus. This is the faith—this is the relationship—we should all be building with the Savior. The answer may not always be yes, but it is never an imposition to ask in faith and to know we are entitled to God’s grace and God’s power.

Our last glimpse of Mary, she is silent, though her actions cause a stir. Sometime after Lazarus is returned to life, Jesus returns to Bethany and has dinner at the siblings’ home. Again, Martha cooks. (For some of us, feeding people is the best way we can show love.) Mary slips into the room where the men are eating. She anoints Jesus’ feet with expensive ointment, then uses her hair to wipe his feet. The room fills with the scent of the oil (John 12:1-3).

If you can get past the 21st-century awkwardness of such a scene, imagine Mary in this moment. She has something of great value to give to her lord. She is in a room full of men, where she is not entirely welcome. And her gift is an intimate one. To do what she did is an act of real love and devotion. And then, in the midst of this sacrament, Judas Iscariot’s voice breaks through.

“Why,” he asks, in what I’m assuming is an unctuous tone, “was not this ointment sold for 300 pence and given to the poor?” (John 12:5)

In one sentence, Mary’s sacrifice—her sacrament—is devalued. She is shamed, told this was the wrong thing to do, that the better part was to take care of the poor. Her act of selfless love and service is twisted into selfishness.

Judas, of course, was wrong. Jesus is quick to tell him that. He commends Mary for her act of love. Mary of Bethany is an example of the kind of quiet, unyielding courage needed to do what you know is the right thing even when it is uncomfortable, even when you must stand alone among people who are supposed to be your friends.

Mary, mother of James, Joseph and Salome

Mary was one of the women who followed Jesus. We don’t know much about most of these women; history tells us they provided financial support for Jesus and his apostles. Mary was the mother of three disciples and possibly the wife of a disciple as well as being a follower in her own right. We know she stood “afar off” and watched the crucifixion (Matthew 27:55-56). We know she followed the hasty procession that carried Jesus’ broken body to the borrowed tomb and that she joined Mary Magdalene at the tomb that Sunday morning to anoint the Savior’s body with herbs. The author of Luke tells us she was among the women who hurried to where the apostles were staying to convey news of the empty tomb (Luke 23:55-24:10).

We know she was steadfast. There are few mentions of Jesus’ apostles on Calvary, but each of the gospel authors record the group of faithful, grieving women who watched from some distance as the Savior suffered. Mary certainly did not come to this place in her life lightly, and her witness of Jesus’ suffering is significant. She probably, in that moment, did not understand what she was witnessing; none of Jesus’ followers understood the atoning sacrifice yet. But they knew he was suffering unjustly. He had done nothing to deserve such treatment. He was the best person they knew.

Being a witness to suffering matters. It offers a chance for empathy, for understanding, for clear-eyed insight into the true cost of something. It recognizes the pain of the sufferer and acknowledges their humanity even amid suffering. It whispers to them that they are not alone, that they will not be forgotten. It connects the witness to the one who is suffering. Just as standing in Auschwitz makes the Holocaust real, walking the fields of Normandy or Gettysburg makes war real and knowing the names of the dead in a mass shooting makes their lives real. As disciples, we should not close our eyes to the suffering of others. It is one way in which we mourn with those who mourn.

Mary, the mother of James, Joseph and Salome, did not avert her eyes that terrible day. Her great love and great pain are not commensurate with the few words given to her in the record. It is no less real for all that.

Mary Magdalene

The final Mary is, of course, Mary Magdalene, the first witness of the resurrected Savior (John 20:1-18). But before there was joy, there was suffering. Imagine the pain Mary must have felt during the Crucifixion. Jesus, whom she loved, was suffering immeasurable pain. She watched as he was whipped and mocked, saw him struggle to carry the heavy cross up the hill, taunted by an angry crowd. She watched as his friends left him. She watched him be nailed to a cross, raised up next to common criminals as if he had not preached a message of love and hope and forgiveness. She watched as the life drained from his body, as the soldiers gave him vinegar to drink, as they cast lots for his clothing while he died above them. She may have heard his last words, commending his spirit to the Father, forced out of lungs that were unable to fill with air. She watched as his bleeding, bruised body was taken down from the tree and spirited away to a stranger’s tomb, as the heavy rock was rolled in front of the door.

Mary had one final act of love to offer. When the Sabbath was over, she and other women returned to the tomb. They would wash his body of the blood, dirt and indignities he suffered, then anoint it. Then she would say goodbye.

But it seemed there was one more indignity—the rock gone, the tomb empty. This one last show of love was ripped from her. Imagine the despair that faithful woman felt as she stood alone at the empty tomb after the apostles had come and gone. Who wouldn’t weep alongside Mary as she mourned the loss of all she’d held dear?

Despair, hopelessness, feeling lost—many of us can relate to Mary in that moment that she stood by the tomb, with no idea of what would happen next. We may have lost loved ones to sickness, carelessness or violence, watched unjust suffering, suffered greatly ourselves. Every day, we hear news of senseless gun deaths, terrible wars, refugees who died fleeing their ruined homeland. It is not hard to put ourselves in Mary’s place.

But joy came in the morning. A man approached Mary in the garden. Here, perhaps, was someone who could explain what had happened, who could assuage at least the grief of not knowing. Imagine reaching out with one last shred of hope in response to the man’s query about why you weep and whom you seek. She pleads with him: “Sir, if thou have borne him hence, tell me where you have laid him, and I will take him away.”

I imagine a slight pause here, a beat where Jesus and Mary look at each other. She doesn’t recognize the changed man in front of her. He, seeing his most faithful disciple in agony, knowing for whom she weeps and for whom she seeks, identifies himself, but not by saying his own name. Instead, he says hers: “Mary.” And her eyes are opened.

My friends, the promise of eternity that Mary heard in her own name is available to us all. Imagine, if you will, the Savior of the world speaking your name—the unconditional love and the promise of eternity infused into the Savior’s voice as he calls you. Even more beautiful than this knowledge is knowing that the Savior of the world knows the name of each of us—he does not differentiate by race, gender, sexual orientation, immigration or socioeconomic status, whether you are trans or cis or the language that you speak. Jesus Christ sees us individually, he loves us unconditionally, and the four women I’ve talked about today, as well as so many other women in the Bible, will lead us to his love as long as we are willing to follow in their footsteps.

3 Responses

Beautifully stated. Thank you for a “sermon”

I want to save.

This is a beautiful sermon. Don’t know if you have seen this sermon by Diana Butler Bass – a very interesting hypothesis (that would add anothe Mary to your list).

https://dianabutlerbass.substack.com/p/mary-the-tower