By Kristin Lowe

February 4, 1980. The credits began to roll on the Phil Donahue show. Director. Executive Producer. Senior Producer. Superimposed titles and names washed over General Relief Society President, Barbara Smith. She sat next to her sister in arms, Beverly Campbell, poised to answer Donahue’s final question of the hour. Smith maintained the visage of what a New York Times article described as the “Hollywood version of the glamorous grandmother.” Silver bouffant hair. Modish suit. And, “homespun manner.”

Smith had spoken out against the Equal Rights Amendment, and for continued progress in women’s rights, nearly since the day she was called as the 10th General Relief Society President in October 1974. On the nationally televised Donahue show, Smith was more practiced, more articulate in her anti-ERA stance than her Times interview two years prior. The audience applauded her take on women’s role in protecting the family.

But, when Donahue asked his final question, “What has the Mormon Church done for women in general?” Smith’s zeal overcame her, and according to several LDS women who watched the program then, her homespun calm showed signs of unraveling. She nearly shouted as the credits rolled, about Mormon women who could bake their own bread! and can their own food for the winter!

Even as Smith’s exclamations solidified Mormon women in the public conscience—broadly tracing over the lines of popular Mormon women caricature as simple-minded housewives—homemade bread and tidy rows of canned peaches became both promise and threat

I make homemade bread weekly. I’ve canned food. Apple sauce, once. Blackberry jam, once. And a botched batch of tomatoes, once. Smith’s argument made 40 years ago sought to define traditional families—tying women to the home—and protect women from the “too-broad,” “too vague,” “too non-definitive” ERA. But these domestic acts do not define what the Mormon church has done for me as a woman; for what it has done for anyone of us. There is a life, a duty really, we are called to outside the home and away from the hearth

After the Women’s March in 2017, there was a new push to constitutionalize the ERA. The old spirits of 70s feminism and conservative opposition reconjured like dust blown in a swirl off an old book. Born in 1985 after the deadline for the ERA’s ratification had passed, I was new to the story, new to the church’s uncomfortably overwhelming political response. I was drawn to the intoxicating scent of a bone still unpicked; a fight still un-won.

Our history tells of early Mormon mothers, who Smith named “the greatest suffragette leaders of the past.” They were called first to scale mountains, nurse the sick, bury their dead, feed the needy, sew clothes and tie quilts, raise money for church buildings and maintain them after they’d laid brick on mortar on brick. Their call to political involvement was seen as a natural outgrowth of ritualistic domestic acts and smart economy.

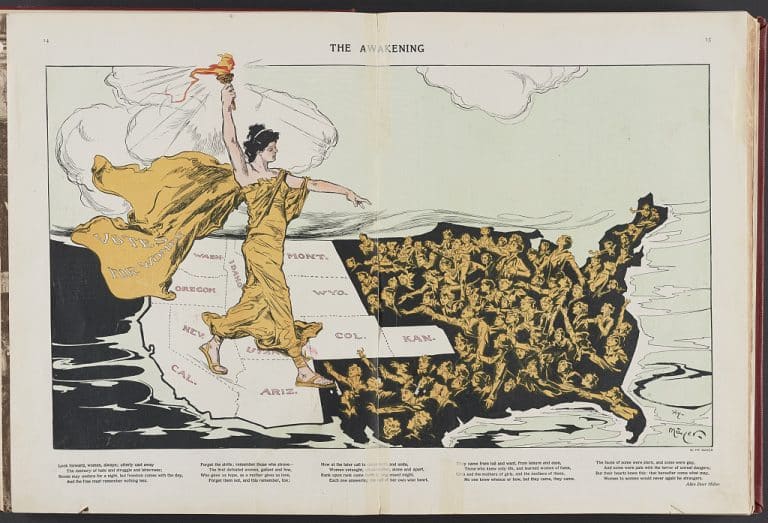

They left home to fight for suffrage. Suffrage was granted in 1870, taken away with the Edmunds-Tucker Act passed by Congress in 1887, and reestablished with Utah’s statehood in 1896. Mormon women, with all the underlying complexity of their loyalties to both church and state, still set out to establish national precedent. Those Mormon mothers were thinking of their return home all along. Of those daughters and sons who occupied the holiest of spaces and would one day go searching for their voice, for a say, in the text of the land and their lives.

Mormon women also had their say in the lively decades-long debate over the ERA ratification, and whether or not the 14th amendment already granted sufficient protection, sufficient equality. Within the church those voices fell on both sides. Although one side sat more comfortable and populous than the other, as support for the anti-ERA movement became analogous with obedience to the prophet. For Mormon women, the ERA became a moral issue. A search for a ratification of Truth to hang their hats, and the law of the land, on.

Mormon women were called by church leaders to act in a political arena. And so, they did what they had long practiced. They organized. They called. They gathered to the Salt Palace on a weekend in June 1977 for Utah’s International Women’s Year conference (IWY). The event planners expected 4,000. 14,000 came with disastrous effect. It was crowded and sticky-hot, and despite thoughtful planning, it soon became a political battleground with Mormon women booing and shouting down speakers. Most came to practice obedience more than to practice any real personal political resolve. Many later stated that they came with feelings of distrust and suspicion but couldn’t exactly say for certain what for.

Across the nation, Mormon women debated. Some questioned. Some wondered. They voted and thereby they obeyed. Or disobeyed. Mormon women proved their ability to organize swiftly around national political moments and influenced the outcome of elections and ratification of amendments.

In a New York Times story that followed the IWY, Smith first conceded that right-wing extremists had “somewhat” used Mormon women to further their political agenda, and then added, “But the thrilling thing about the meeting was that our women went home anxious to know more about the concerns of women. I was so thrilled with what happened there that I encouraged our women in other states to attend their conventions.”

Smith’s self-understanding was congratulatory, even while admitting to the larger public understanding that extreme groups have a frightening negative influence that threaten to take political neophytes unaware.

The issue of winning back their right to vote united Mormon women in the late 1800s. Their freedom came in starts and stops. Beginning in the 1970s and continuing today, we struggle with how Mormon women use that power to vote. We wonder at the powerful outside voices that influence those votes. We still see the fractures and feel the fear born in the 70s. Fear over the blank spaces we tried to read between the lines of the Equal Rights Amendment, and the fractures that marked the aftermath of voting against religious lines.

Mormon women’s political history with the suffrage movement and the ERA is instructive as I move forward in the 2020 election year. There is room for Mormon women to see civic and political truth differently, to celebrate the divergence of opinion among us as a healthy political state and use our moral principles to guide us to individual truths at the polls. But history has taught me to check not just ballot boxes, but the authenticity of my vote. I recoil from being “somewhat used” on any point of the political spectrum.

So, Phil Donahue, four decades later the real answer to your question is: we might let the bread rise too long and the fruit sit awhile. The Mormon church has organized a community of women ready to engage collectively in causes larger than ourselves. We gather to protect the interests of those whose needs might be otherwise overlooked. That help most often translates to women caring for other women. Women of every color and ethnicity and socioeconomic clime. We are still the least of these. We still need voices. And knowledge. And votes.

Kristin Lowe holds an MFA from the University of Georgia’s Grady College of Journalism and works as a freelance writer. She is a believer in the unifying power of feminism.

2 Responses

This post is so well written – thank you for sharing here! Please write for us again! I love how you put it all together.

Well done Kristin! ❤️❤️