Growing up, the most coveted costume in our nativity box was Mary. Unlike the other ramshackle pieces—a few foil-covered cardboard crowns, some tinsel halos, a couple of old bathrobes, and half a dozen shepherd’s headdresses made of hand towels—Mary’s costume was an unblemished band of smooth, blue fabric. When it was double-looped, it made both a hair covering and a maternity robe, easily concealing the smudgy plastic baby doll that would miraculously appear as the Christ child just seconds after Mary settled in at her makeshift stable.

We had only one Mary costume, which seems appropriate as there’s only one Mary in the scene. But we were family of six girls, and we each wanted to be Mary every year.

We didn’t say so, of course. Saying you wanted to be Mary was the least Mary-like thing you could do, which meant you were less likely to be given the role. Instead, we pawed through the costumes, each of us running a hand over the blue fabric, pretending not to care who would be wrapped in Mary’s robes that year.

There was no rotation, no method to ensure that all was fair and equal in the casting of Mary each year. I seem to remember my older sister playing Mary more often than not, though we each had our turn eventually. The sisters who were not in the Holy Family had to double up on parts, so I came to identify myself as both a shepherd and a wise man in order to steel myself against the disappointment of not being Mary. Again.

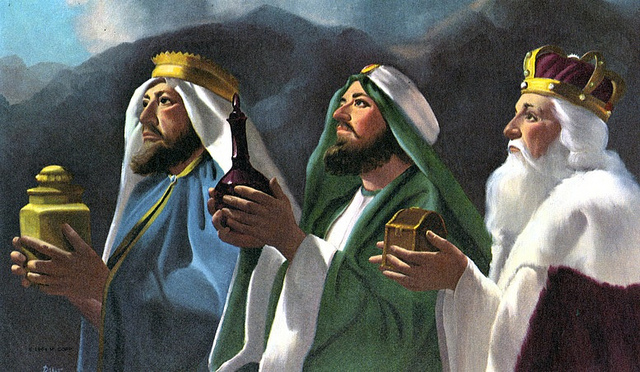

We tried to feminize the other parts as much as possible. We dressed the angel Gabriel in a shimmery white skirt, pretending that he, too, was a female lead. We had a female innkeeper, wise women from the east, and shepherdesses watching their flocks. The only one explicitly male character was Joseph, and his part was often performed by my dad, decked in his own brown bathrobe and head towel.

Our Nativity was not what you might call accurate, but it was performed with love and reverence, despite our lack of men and boys. It remains one of the most spiritually potent rituals of my youth.

And yet, as an adult, I can’t help but quarrel with the casting.

Like so many of our roles in Mormondom, most of the important parts are played by men. In our art, our hymns, our primary songs, women don’t wear crowns, halos, or shepherd headdresses. Women are the background extras, the characters most easily cut from the mise-en-scène.

This is why Mary’s existence is something of a miracle in the Christmas story. In a religion that revolves largely around male characters—male Savior, male God, male priests, male prophets, male apostles, male writers and translators of scripture—Mary is one of a handful of women we actually celebrate at church.

And yet, our depictions of Mary are still largely patriarchal. The Mary of Mormonism is largely a glorified vessel for the divine. Sure, she displays a few admirable qualities: willingness to serve, tenderness, and at the very least a parent’s instinct to wrap a baby in something and to set it down somewhere safe and not-on-the-ground. Other than that, we don’t know much about her. She’s mostly absent from the Biblical narrative. We might read descriptions of her whereabouts, but we don’t hear her voice or see her actions.

Then, of course, is the issue of her virginal status. Like many women, Mary has been used to police sexual purity among Christian women for centuries. She sets a literally impossible standard for women to achieve: become mothers, she says, but not through sex. I sometimes worry that by venerating Mary, I’m not celebrating the many other meaningful identities available to women outside of maidenhood and motherhood. Instead I worry that I’m simply propping up the machines that have kept women underfoot for most of human history.

And yet, I can’t dismiss Mary. She remains one of the most mysterious and revered women in religious history.

She gave birth to and raised God, which sets her in a world apart from other scriptural heroes—above priests, apostles, and even prophets. In other denominations of Christianity, she’s often celebrated as a universal mother figure. She’s wise, kind, and forgiving—a compassionate intercessor on behalf of all humanity in the face of sin and evil.

But Mormons don’t worship Mary—not in the way many other Christians do. To us, she’s a revered woman, though no more perhaps than Eve or Sarah, Esther or Ruth. And though we might think of them fondly, we do not approach them in prayer or worship them. And yet, to me there’s always been something different about Mary.

On the one hand, we have the historic Mary, the one patched together by Biblical scholars. Except for the bare fact of her existence, scholars tell us that Mary is almost completely invisible from actual historic records. We can speculate about her life and origins, but we don’t know her.

On the other hand, we have Mary from Mormondom and Christianity. This Mary is a sweet and tender young woman who loved God and loved motherhood, both admirable qualities. She was a “precious and chosen vessel,” a singer of lullabies, a woman who “kept all these things and pondered them in her heart.”

But there’s a third representation of Mary that rides the undercurrent of feminist Mormon spirituality. That’s the role of Mary, Holy Mother, a woman Tresa Edmunds calls the “closest avatar we have to our heavenly mother.”

To me, this representation is at once the most satisfying and the most heartbreaking—an apt duality in her nature. This is the representation of Mary that sees her as a version of Heavenly Mother herself. This depiction is satisfying in the sense that I finally see deity wearing the robes of womanhood. It’s an acknowledgement that I’m the daughter of Heavenly Parents, not simply a motherless child in the scheme of divine existence.

And yet, it’s heartbreaking, too. I see so little of Heavenly Mother represented in my religious tradition that I grasp at even the smallest resemblance. This cracks open my heart in a different way. I should be able to see representations of my actual Heavenly Mother at church, to speak freely about my spiritual experiences with Her, to pray to and worship and revere Her in the same way I do my Heavenly Father. Mormons should speak of Her, we should know more of Her nature and Her works. When I see Her in Mary, I cling to Her image. I tease it out. I even play-act.

In this way, I feel I almost know Her, though I want to know Her better. Always. I want to see myself reflected in Her divinity, to wrap myself in Her smooth blue fabric, to draw on Her endless wisdom and goodness. I long to be mothered by Her, to drink deeply of her love, to stand rooted in Her wild power. And though She’s still nothing more than shadows on a cave wall, I’m learning to be like Her, to follow her dance, to find myself sung in her deep and sacred song.

5 Responses

Thanks for your thoughts. They resonate with me. Also, what can you tell me about that last painting of Mary holding Jesus?

This was a beautiful piece, and will give me something to think about this Christmas. I realized while reading it how much my view of Mary (and other scriptural women) has been filled in by my own imaginings; it really is heartbreaking how much we have to do that because of how little we know about them. And, of course, this ultimately applies to our Heavenly Mother, and I fully agree we need her more in church life and representation. Thank you so much for sharing this!

Thanks for this. I feel like Mary, rather like all mothers, tends to get swept aside the instant the baby appears. She’s sacred and fussed over and important until the baby comes, and then everyone just fusses over the baby. “You go over there and bleed and cry and lactate. I’ll hold the baby.” say the wise men and shepherds and angels. Her invisibility is our invisibility. Motherhood is sacred — go do it in an airless closet so nobody sees your breasts. As we slowly reclaim identity within motherhood, perhaps Mary emerges with us.

Beautiful piece – thank you. I was raised to have contempt for how Catholics worshipped Mary. Now I see that worship as beautiful and powerful and its oppression just more patriarchy. I also long for my Mother and it tears at me that in Mormonland it’s heresy to seek Her.

FYI, Catholics do not worship Mary. Worship is reserved for God, in all three persons. Many Catholics love and honor Mary, but it’s not worship.