Guest post by Lynnette. More of Lynnette’s bodacious writing can be found where she blogs regularly at Zelophehad’s Daughters.

In John 4, we find the encounter of Jesus with a Samaritan woman at Jacob’s well. Jesus and this woman have a lengthy dialogue. Because it is revealed in the course of this conversation that this woman has had five husbands and is currently with a man who is not her husband, this story has often been viewed through the lens of female sexual impropriety. In a common interpretation, Jesus demonstrates supernatural knowledge of her dubious situation, and she tries to wriggle out of the resulting awkwardness by bringing up theological questions.

In John 4, we find the encounter of Jesus with a Samaritan woman at Jacob’s well. Jesus and this woman have a lengthy dialogue. Because it is revealed in the course of this conversation that this woman has had five husbands and is currently with a man who is not her husband, this story has often been viewed through the lens of female sexual impropriety. In a common interpretation, Jesus demonstrates supernatural knowledge of her dubious situation, and she tries to wriggle out of the resulting awkwardness by bringing up theological questions.

This popular read, however, does not do justice to the story. I draw here on the work of Catholic feminist biblical scholar Sandra Schneiders, who proposes a feminist interpretation of this account. (See Sandra Schneiders, The Revelatory Text: Interpreting the New Testament as Sacred Scripture (Collegeville, Minnesota: The Liturgical Press, 1999)) Schneiders points out that this is a “type story,” along the lines of that of Abraham’s servant and Rebecca, or Jacob and Rachel, who also meet at wells. “The pattern or paradigm is the story recounting the meeting of future spouses who then play a central role in salvation history.” (187) Jesus is the “true Bridegroom” who “comes to claim Samaria as an integral part of the New Israel.” (187) This is an important context for making sense of the story.

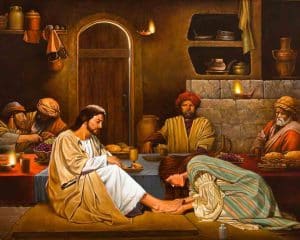

According to the Johannine text, Jesus asks the woman for a drink. The woman responds by inquiring how it is that a Jew is asking this of a Samaritan. Jesus then brings up his ability to offer living water. The woman asks if he is greater than Jacob, and Jesus responds that he can give water which will be a well “springing up unto everlasting life.” (v. 14) The woman asks for this water, and Jesus tells her to call her husband. She replies that she has no husband. Jesus observers that this is true, and comments that she has had five husbands and the man she is currently with is not her husband. She responds with an acknowledgment that he is a prophet, and follows this up by asking where true worship should take place. Jesus speaks of true worship as being in spirit and truth. The woman now brings up the Messiah, and Jesus confirms that that is in fact his identity.

Schneiders observes that the entire discussion here is theological. The bit about the five husbands is not best understood as a kind of tangent, but as a core part of the conversation. And the husbands, she proposes, are actually symbolic. A common way to talk about Israel’s less than faithful relationship to God is with the use of the language of idolatry as adultery, as a betrayal of the covenant. This language would make sense in reference to the situation of Samaria: “Samaria’s infidelity to the Mosaic covenant was symbolized by its acceptance, after the return of the remnants of the northern tribes from Assyrian captivity, of the worship of the false gods of five foreign tribes. Samaria’s Yahwism was tainted by false worship and therefore even the ‘husband’ she now has (a reference to her relationship with the God of the Covenant) was not really her husband in the full integrity of the covenantal relationship.” (190)

This puts the whole conversation in a different context. “Jesus’ revelation to the woman, who symbolizes Samaria, of her infidelity is not a display of preternatural knowledge that convinces the woman of Jesus’ power (and thus her helplessness before him), embarrassing her into a diversionary tactic in an effort to escape moral exposure.” (191) Rather, he is speaking against false worship—a classic prophetic move. Her response, that she perceives him to be a prophet, thus makes perfect sense, and her ongoing questions can be seen in that vein. Schneiders points out that the depth of this dialogue is striking, and unique in John. Notably, the woman “is a genuine theological dialogue partner gradually experiencing Jesus’ self-revelation even as she reveals herself to him.” (191)

A further interesting note is that the woman leaves her water jar, and goes to tell people about her experience with Jesus. “Like the apostle-disciples in the synoptic gospels whose leaving of nets, boats, parents, or tax stall symbolized their abandonment of ordinary life to follow Jesus and become apostles, this woman abandons her daily concerns and goes off to evangelize the town” (192) In other words, the woman functions in an apostolic role. (Schneiders proposes that the author of the fourth gospel is likely familiar with women functioning in such roles, and here seeking to legitimize this.)

The woman at the well is thus a powerful story. It is not a tale of Jesus showing off his knowledge of the moral failings of a woman who reacts with embarrassment and attempts to change the subject, but a rich theological exchange. As Schneiders puts it:

The reader cannot fail to be affected by the fact that the recipient of Jesus’ universal invitation to inclusion is a woman, universal representative of the despised and excluded ‘other’ not only in ancient Israel but throughout history and all over the world. Not only is she included, but she is engaged with respect, even asked for a gift (water) that she might receive a greater gift (living water). Her legitimate inquiries, even her objections, are met and responded to with integrity. And even more strikingly, she is made an active participant in the establishment of the universalist reign of the Savior of the world. (196-7)

10 Responses

Thank you so much for this, Lynette. I love this way of looking at the story, and feel more empowered by it. It’s made me question which things I might “worship” before I worship the Lord and how I can improve. Many, many thanks for this important contribution!

Wow. This kind of blew my mind. I love this so much.

Interesting stuff, Lynnette! I had no idea about any of this. Thanks for sharing it!

Also, I love your line where you say “he is speaking against false worship—a classic prophetic move.” Perhaps it’s because I’ve seen my kids playing Super Smash Bros too much recently, but this totally makes me think of a version where prophets square off against each other, and one of them smacks another one down by speaking against false worship. Ha! It’s a classic prophetic move. 🙂

I love this so much, Lynette. I’m glad to learn from you.

This whole series has been amazing. Keep up the good work, everyone!

This is brilliant. Just brilliant.

[…] the woman at the well who has a theological discussion with Christ before going on to proclaim to others, “Come, see a man, which told me all things that ever I did: is this not the Christ?“ […]

[…] There are many accounts of women interacting with Christ in the New Testament. In the story of Mary & Martha receiving Jesus at their home, we read of women not only serving Christ, but learning at his feet as men did in that time. In the story of the woman with the issue of blood, we read that women sought Jesus to be healed. In the stories of the woman who was “bowed together” and the Widow of Nain, we read that Jesus healed even those who didn’t directly seek him. In the story of the Samaritan woman at the well, we read that Jesus discussed theology directly with women, breaking many cultural and religious customs of the day (read Lynnette’s brilliant thoughts on this story here). […]