By Aly H

By Aly H

I didn’t begin to realize that I was a feminist or that it was my Mormon faith that had made me one until just a few years ago, as I sat through two awful, sacred hours in a new white temple dress.

As a Mormon girl born to Mormon parents in a predominantly LDS community, I had grown up quite aware that things were often different for men and women in the church: that it was always and only men conducting our meetings and overseeing the ward goings-on; that it was men and only men that could baptize and confirm me, interview me and give me the OK to participate in temple baptisms, set me apart to fulfill my Young Women’s callings, and place their hands on my head to give me blessings of healing and direction.

But the ever-present differences in opportunities given men and women felt, for whatever reason, peripheral and irrelevant to me as a Mormon girl.

Rather, what I saw and deeply internalized growing up in Mormonism was that my then-current opportunities to lead and direct and serve within the Church, aside from blessing and passing the sacrament (which never gave me pause), seemed unhindered by my gender.

What I saw was my strong Mormon mother—an incredible organizer, motivator and beautifier, as she actively participated in positions of power and service both within and outside of the Church—and the happy marriage she and my Mormon father modeled for me.

And what I saw was the authentic, faithful female leaders I had in young women’s and seminary (the only seminary teacher I ever had was a woman), who had a far more direct and powerful impact for good on my life than any Bishop or home teacher or other male leader.

At home and at Church, what I saw and internalized were the constant reminders I was given of my infinite worth and strength, and of my ability and obligation to seek direct access to Heaven as I made decisions for my life. My interactions with Mormon theology and practice and people taught me to be humble and kind and strong and bold, to see myself and others the way that Heaven does—as precious, glorious, and equally loved and important to God—and to act accordingly. And as I learned that my female identity encompassed not just my physical body but also my spirit, and not just now but forever, I developed a sense that being a woman was to possess power and capacity –unique but equally as vital and divinely-bestowed as the power given to men.

For me, being a Mormon girl was both easy and affirming; and the vibrant beliefs I internalized and took for granted permeated how I saw everything—even heaven.

When I used to think of heaven in those easy days, I had in mind the traditional Christian image of singing praises to God in heavenly choirs (alto section, please), but the Mormon theology I saw led me to also imagine Heaven as a celestial version of a gorgeous university campus, where my days would be spent taking rigorous courses taught truly and beautifully in big, sparkling lecture halls. I imagined evenings catching up with fascinating ancestors on long runs over celestial mountain trails, and Sunday dinners discussing the mysteries of the universe with my wise, strong, totally-in-love Heavenly Parents. And above all, the Heaven I imagined was a place where I would continue to learn and love and work alongside my future husband. I knew within me that this stellar guy and I would be equal, mutually-dependent partners in awesomeness. And as a young girl growing up Mormon, the ubiquitous patriarchy never led me to consciously worry that heaven’s beauty, wisdom and power would be more accessible to a man than to me.

While heaven was one of the goals of being faithful, of understanding my divine nature and individual worth, of gaining knowledge, making good choices, serving others and having integrity, I knew that the way to get to heaven was to go to the temple: to “be prepared to make and keep sacred covenants” there, which covenants would enable me to “enjoy the blessings of exaltation.” As a youth, I was repeatedly taught to “always have the temple in my sights,” and that it would be there that I would learn more about God, about Heaven and about my eternal destiny, and experience peace perhaps unlike anything I’d ever known.

Oh how terribly surreal it was, then, when my first-ever temple session ended and I stepped into that celestial room full of beaming family members waiting to hug and congratulate me, feeling like I did.

Because all of it, it seemed—my beliefs about Heaven, God, and my worth and place in eternity—had been brought down and crashed all around me.

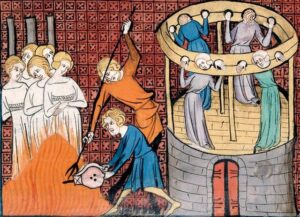

Over and over in that celestial room and in the hour and days and months that followed, I mentally replayed parts of what I’d seen: a weak and robotic Eve partaking of the fruit[1], who is then commanded to look to and obey her husband, who made no such promises to her, and who would, it seemed, be her Mediator, her access to God and hope for gaining Heaven—and how unsettling yet fitting it had been that afterward, she never spoke nor was spoken to again in the film. I remembered the shock of seeing Heavenly Father rule and decide and create alone, or only with the help of other men (great men to be sure, but males only). And I wish I could describe how deeply my heart had ached to see some evidence of Mother, of Her love for and involvement in the lives of Her children. But she was hidden or gone or nonexistent, worth only the vaguest of references even in the Holy Temple. Why wasn’t She reaching out to Her children, too? Would I also disappear in Heaven?

In the space of two hours, it seemed that every one of my most cherished beliefs, directly or indirectly, had been contradicted and sent packing. And in the spaces they once filled, I was flooded with questions, doubts, and a depth of sadness and loss I’d never experienced.

Along with those questions came an immediate and desperate desire to find resolution to them—to learn definitively whether it was me or this Church I’d loved my whole life that had it terribly wrong here. This search for answers began right away as I cried and blurted out questions for an hour in one of the temple matrons’ offices. She was kind and well-meaning and sincerely wanted to help, but admitted that she had never wondered or worried about those things herself, and had no answers for me. And as I went back and back and back again to the temple, I left again and again with feelings of despair and frustration that what I was seeing did not match up to what I felt within me was true—to the esteem and love I had felt throughout my life as I’d brought my troubles and gratitude before Heaven, with the rightness that so obviously accompanied the strong, connected, very much mutually dependent marriage I’d entered into a few days after that first jarring temple experience, and with what I’d always believed to be at the beautiful core of Mormon doctrine.

It was after that first time going through the temple that things began to look different to me.

General Conference did, with its sea of black suits and almost-always male speakers.[2] So did seeing twelve-year-old boys, newly ordained to the priesthood of God and passing the sacrament—the most sacred of ordinances—while it seemed that their female counterparts were simply given more lessons on modesty and marriage that would too often overemphasize appearance or promote a “too-narrow narrative” that not every girl will be able to achieve or find happiness in.

Now, I felt only confusion whenever I tried to understand the Proclamation’s claim that women are equal to men and men are in the position of authority (“preside”) in the home, and the uncomfortable ways we Mormons sometimes try to normalize unequal, hierarchal marriage relationships (like in the anecdote used at the beginning of this talk).

I began to cringe inside every time I heard women brush off the female ordination topic with the “I wouldn’t want the kind of responsibility my husband has!” response, and I felt sick when I heard or read attempts to shame and belittle and ostracize those sisters who felt differently.

Now, I started to feel uncomfortable about the fact that teenage girls (and women in general) aren’t at least routinely given the option of having another female present when confessing sexual sins behind closed doors to their Bishop (likely an uncomfortable situation for him too)—and that women are not allowed to be part of the council that makes disciplinary decisions even when it is a woman that is being tried.

I was surprised when I learned that the Relief Society had once had incredible amounts of autonomy in matters like how they would spend their money and what lessons they would teach, and was even more surprised to learn that women had at one time been able and encouraged to anoint and bless family members and their fellow sisters by the laying on of hands.

And then there was polygamy—all it threatened to take or cheapen, and all of the unresolved insecurity, revulsion and fear I’d thus far managed to bury and ignore. Like so many things, the temple forced polygamy to the forefront of my mind, and for me it was a chilling notion that frequently left me in desperate, resentful tears—even newly married to my husband, who adamantly reassured me that he felt the same way; that I was his equal, and that he would never do that to me.

And as I began to realize more fully these differences between the opportunities and powers given to men and women in the Church, I became pregnant with a baby girl. And as I felt her kick inside me and eventually held her innocent little self to me and have since been awed by her spunk and fire, I’ve spent a lot of time wondering whether this patriarchal Church is where I really want to raise her. To be quite honest, I don’t know that I’ll ever stop wondering.

For me, the temple threw so much of what I’d held dear into upheaval. But the pain of all of that has changed and deepened me, I believe. And for me, working through all of this has led me not away from my childhood faith tradition but back to it: different, more roughed-up than I was before, but here nonetheless, hopeful and striving.

To suddenly and quite completely have to rethink and remember and relearn in one’s faith journey is an experience many understand and yet all of us respond to differently. I cannot overstate this: my sincere belief that faith, reason and integrity can lead good people down very different yet equally valid and meaningful paths.

And thus far, my path includes staying Mormon. And for me, it’s both despite and because of the messiness and the mistakes and the heartaches that I stay. I stay because Mormonism is my spiritual home and language. I stay because something quiet and expansive and lovely within me urges me to choose to believe in the existence of a God, and in a God who knows our hearts, who is the perfect embodiment of that which is most noble and good within us, and who grants us strength where our own would otherwise fail us. And I stay because of the ways that I can find encouragement and growth in this imperfect, learning faith tradition.

And, acknowledging my worries for her, I stay because I hope to raise my daughter in a faith tradition that teaches her that she has direct access to Heaven. That teaches her that family connections are sacred and eternal, and that God is both Father and Mother, together reaching out to guide her and all of us home. I want my daughter’s religious experience to involve opportunities to lead and serve and collaborate, and for her church to teach her to listen to the still small voice of her nature’s better angels—to “think and discover truth for [herself]…., to ponder, to search, to evaluate, and thereby to come to [her own] personal knowledge of the truth” (Uchtdorf, 2013). And when I think of the refinement and growth made available to me by striving with other imperfect believers, the clarity and sweetness that have come into my life as I’ve pondered and applied scripture and inspired words of Mormon leaders, and the peace I’ve felt as I’ve sought out and exercised faith in a Savior whose grace is undiluted by my dust and sin, I want my daughter to have access to those same opportunities.

I stay because when it comes down to it, I feel that truth and goodness are present and alive within Mormonism, even if many parts of how we walk and talk haven’t yet caught up to much of the beauty we possess.

So, that is some of why I stay. But perhaps a more interesting yet difficult question to address is how I stay—what I do to not just hang on but thrive in this no longer assumed and simple path.

As I share some of how I stay, please note that I recognize that I’m new here—that I’m inserting myself into a discussion that began decades and even centuries before I was around. I haven’t read or grappled with or experienced as much as many of you have, but I’m writing this nonetheless, compelled by the increased clarity that writing offers, and by the hope that doing so might offer something usable to someone else who’s felt like I have. What I present here, then, is where I’m at and what has worked for me.

(Part II of this post will be published tomorrow.)

[1] This film has now been replaced by a few others, one of which in particular, I think, offers a more affirming interpretation.

[2] In the October 2016 General Conference, 32 of the total 37 talks were given by men—about 85%. In April 2017, 32 of the total 36 talks were given by men—about 89%.

17 Responses

Beautiful post, Aly H. I had serious questions about gender before I went to the temple, but like you, my world shattered when I did go to the temple and really listened to the language. I sobbed throughout the endowment and sobbed for hours after. I have never felt such despair. I wonder how many others have experienced something similar.

“I have never felt such despair.” Yep. And whether women pick up on the language the first time or years later, it can be so hugely devastating. Have you ever written something about your experience going through for your endowment? I’d love to read it.

Oh my gosh. That conference talk. ?

No kidding!!!!!

Looking forward to part II!

Thank you for your post! Yes, the temple endowment desperately needs to change. It should reflect that there will be gender equality in the afterlife and should not leave people guessing or crushing their hopes. I don’t like doing sessions or proxy sealings because of the different wording used for men and women. It’s so upsetting. If they only changed it, imagine what a better experience it would be for women. And I’m sure women would go to the temple more often if the wording was changed to show gender equality.

I sometimes wonder how Mormon women (and men!) would respond if changes were made and equal language was used in the temple–if more would attend (or less), or if most people wouldn’t notice or feel that strongly about the change (my guess is that most would fall into the “meh” category, but I could be totally wrong)

Aly, I’m so glad that you posted this, and my journey is very similar to yours. Your writing is gorgeous, and I hope you’ll write more with us (and I’m eager to read Part 2)!

This is so well written and speaks perfectly to my experience – both the growing up in the church feeling fairly empowered, and the feeling shattered and depressed when the temple narrative tore apart my beliefs about my relationship with Deity. Thank you for opening up about all of it. Looking forward to tomorrow’s post.

Thanks, Valerie. I’m so glad it resonated with you.

This is so lovely. I could have written this, except that I always struggled with the differences in opportunities given to boys vs girls. Thank you for sharing here! You explained the inequity so perfectly.

This was beautiful. That picture of your 8 year old self reminds me of my baptism pictures. I wish I could hug that 8 year old version of me and congratulate her on her baptism. I loved that day. I wish I could be there when younger me left the temple after her endowment and hold her. I hated that day. Despite being surrounded by family and loved ones. I’d tell her how sorry I was, and that while nothing is going to make it ok, the act of searching for answers will stretch you and help you empathize with those for whom church is hard. Maybe that’s what I was supposed to learn in the temple.

Yes, empathy is one of the most important things the temple did for me, too. Because to be honest, I could be nauseatingly self-righteous sometimes. 🙁 I needed a fat dose of humility before I could learn to be more kind and helpful to others who for whatever reason don’t feel like they fit in with our Mormon culture.

Thank you, thank you, thank you for giving a voice to my painful feelings and thoughts. You are giving me courage!

Amen. I do not have your wonderful way with words, your expressions in this article are similar to my own experiences. Thank you for sharing them.

YES! I appreciate you opening up about this. I was a faithful Mormon girl all my life, but once I hit my mid 20’s, something changed. I’m still struggling with whether to stay (I’m “taking a break” at the moment), but I appreciate knowing that others feel the same way I do about the temple. It’s so frustrating when people tell you to expect a magical, transformative experience, but you find yourself at a loss because of the inherent unfairness of it all.