“The ‘right’ to life, to ones body, to health, to happiness, to the satisfaction of needs and, beyond all the oppressions or ‘alienation,’ the ‘right’ to rediscover what one is and all that one can be, this ‘right’ was the political response to all these new procedures of power.” (Michel Foucault, La Volonté, p. 191).

For the next few months, I’m going to discuss Intimate Partner Violence (IPV), sometimes called spousal abuse. If you need help in the US, this website has resources. This month, I address physical abuse. TW. These are hard topics, and they bring up challenging emotions. Sometimes, we ourselves have experienced abuse or we love someone who has. And sometimes, we find ourselves wanting to shield the person, usually a man, accused of abuse. I hope we can sit with our discomfort so we can learn to create a world that more fully meets the needs of the most vulnerable among us.

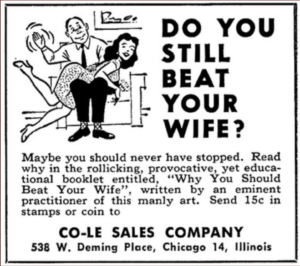

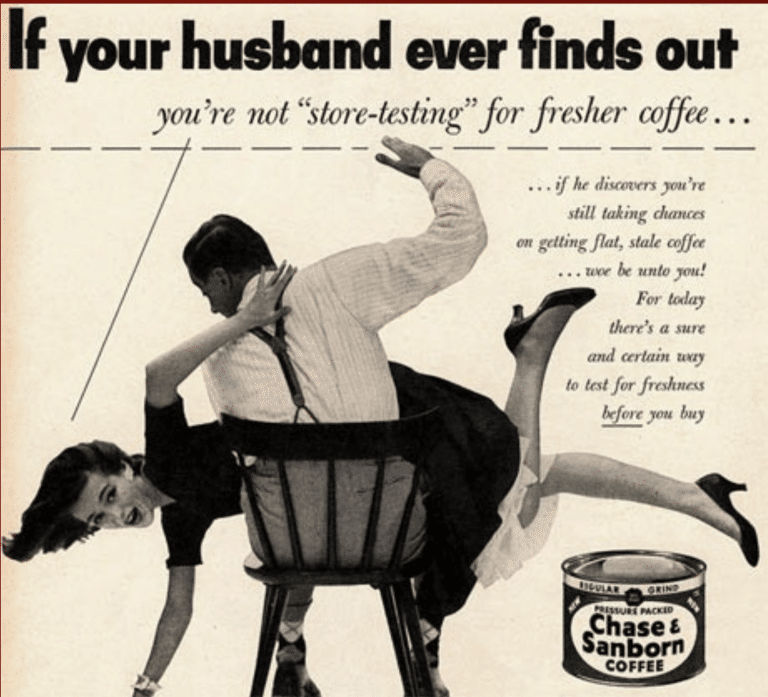

Based on English Common Law, the history of wife abuse in the US is a rage-inducing dive into individual sovereignty and patriarchal control. Religious, social, and legal systems repeatedly reaffirmed the notion that men were kings in their own homes. The legal principle of coverture stated that a wife’s identity was completely subsumed by her husband. This led to some hard-to-hear court rulings. In State v. Black, the North Carolina Supreme Court stated, “A husband is responsible for the acts of his wife and he is required to govern his household, and for that purpose the law permits him to use towards his wife such a degree of force as is necessary to control an unruly temper and make her behave herself.” Iowa put it more bluntly, “…if what is complained of as cruelty is the result of the complainant’s own misconduct, it will not furnish ground for the proceeding. The remedy is in her own power; she has only to change her conduct; otherwise the wife would have nothing to do but misconduct herself, provoke the ill treatment and then complain.” As experts in abuse will tell you, there’s nothing the victim can do that will be good enough: it isn’t about the victim, it’s about power, control, and inflicting pain.

While some courts limited the size of the instrument the man used to “correct” his wife, or insisted that the husband could not be allowed to inflict permanent damage, not all courts took a stance on the nuances, believing that the privacy of the home was of paramount importance, and that a man had the right to rule his home as he saw fit.

Who has the right to own and control another person’s body?

While wife beating is currently illegal in many countries, in reality a vast number of women continue to experience IPV. 1 in 3 women worldwide experience physical and/or sexual abuse. Michelle Bachelet, former UN Women Executive Director, said, “Stopping violations of women’s human rights is a moral imperative and one which we must come together to combat. The impact of such a scourge on society — psychological, physical, and economic — cannot be overstated.” (Read the full statement here.) Some countries, like South Korea, consider partner violence to be a domestic, not legal, matter, making eradication efforts more challenging.

But ending IPV will take effort in multiple spheres and will require prioritizing voices we sometimes ignore. Carceral feminism, the branch of feminism that pushes for judicial responses to IPV, has exacerbated the violence some women face. In “Perpetual State of Violence,” Robyn Bourgeois points out that police rarely investigate cases of missing Indigenous women, courts infrequently charge white men with the crimes, and the women who enter the system through reporting are more likely to face abuse by the police, including incarceration. Kali Nicole Gross voices similar failures to protect Black women and girls: increased racial profiling results in higher rates of incarceration for all genders, which translates into more poverty, more children in the foster care system, and less access to needed resources. In other words, white women, in our efforts to eradicate violence against women, have actually caused an increase in violence against some women.

Historically, violence in the LGB community has been ignored, partly due to draconian laws that banned their relationships, and partly due to fear over how they would be perceived by the heterosexual community. In “When Intimate Partner Violence Meets Same Sex Couples: A Review of Same Sex Intimate Partner Violence,” Rollé et all say, “Our findings show there is a lack of studies that address LGB individuals involved in IPV: this is mostly due to the silence that has historically existed around violence in the LGB community, a silence built on fears and myths that have obstructed a public discussion on the phenomenon.”

In all of these cases, bias built into the policing and judicial systems has exacerbated the threat of violence. White carceral feminism has failed.

“But why don’t women just leave?” some ask. While there are multiple, complex reasons, I’ll touch on two. Many women face religious pressure to stay. Officially, the LDS church denounces abuse in the most forceful terms; in practice individuals and leaders often fail to protect or support women, even counseling them to stay in violent situations. Speaking to an LDS therapist off the record, I was told that the LDS church doesn’t necessarily encourage women to leave abusive situations. “We believe in supporting couples as they work toward a celestial partnership. Therapy can help men control their responses and can teach women to forgive.” (I, personally, find this reprehensible and ill-conceived). On several occasions, Richard G. Scott perpetuated the notion that, as abhorrent as abuse is, the victim has some responsibility (also here). And by now we’ve all heard the stories of how LDS men protect other LDS men at the expense of women and children.

Even when women succeed in leaving, they can still be victims of men who find them and either kill them or force them to return. US court rulings have generally incarcerated women who, when driven to the brink, kill their husbands. In 1989 the Supreme Court of North Carolina ruled that a woman was not justified in shooting her sleeping husband. Married at 14, she had been with him for 25 nightmarish years, during which time they had several children. I won’t go over the details (you can read them here). It’s enough to say that 2 expert witnesses testified she had battered wife’s syndrome, had tried to escape several times and was always forced back by the husband, and that she had come close to dying multiple times. When she sought counseling, she was returned to her husband. When she sought relief through legal avenues, the police turned her away. She didn’t believe herself to be powerless: the courts, police, hospitals, and her husband all played a part in taking away any power she had. When she shot her husband, the court ruled that it was not in self defense because he was asleep at the time she shot him. The court neither understood nor cared about the power differential, the history, nor her state of mind. They only cared that, in a world of men, one man shooting another man had to be narrowly defined in order to be self defense. The laws that may protect men from each other do nothing to protect wives from abusive husbands.

In Mvskoke law, women had only to name the man and what he’d done in order to receive protection and reparation. And what did this justice look like? It depended on the woman’s needs because she also had the right to name the restitution. What would it be like to live in a society that believed wives and supported us as we worked toward healing? Wouldn’t that, in itself, greatly reduce the risk factors and aid in community support if violence occurred? Wouldn’t it help all of us to know that our bodies belonged to us, not just in a religious “God’s Temple” sort of way, but in a tangible, judicial way, and that we could claim ourselves, claim our own narratives and feelings, and have those claims respected?

I don’t think the world as a whole, and certainly not US society, is anywhere close to making this a reality. While we’ve moved beyond ads promoting the benefits of wife spanking, we’re nowhere near getting rid of the fact of it. The truth is, all too often society, laws, and the courts think men have the right to control our bodies: what we do, where we go, how we dress. It’s all connected, and it all comes back to white heteropatriarchy. When we see reports of abuse against women, we need to stop seeing them as flaws in the system. The system functions as designed. It isn’t a bug: it’s a feature.

7 Responses

Such maddening history, but important to know and discuss. So frustrating that LDS church leaders and therapists encourage women to stay with abusers under the guise of protecting the “eternal family.”

Thanks for blogging about this. What a horrifying history and a depressing present, although the progress is encouraging.

The Church’s mixed record, as you note, is particularly frustrating. When GAs say that abuse is awful, that’s great, but they don’t account for the fact that most abusers don’t see themselves as abusers. Simple statements like that are maybe better than nothing, but just barely. As long as they promote a patriarchal model of the family, and things like single-income households, and couples having as many kids as they can (and probably one or two more, just to be safe), they’re contributing to situations that make abuse more likely and harder to get out of. Not to mention generally frowning on divorce and, as you note, supporting abusers over abused and encouraging forgiveness by the abused over accountability for the abuser.

“…they’re contributing to situations that make abuse more likely and harder to get out of.” Amen.

Just as Ziff pointed out, so long as this church worships, above all else, the patriarchally modeled “eternal family,” it will justify sacrificing women and children to maintain it.

And in a state that is predominantly LDS, this headline speaks volumes:

https://www.ksl.com/article/50354436/this-has-got-to-change-in-utah-sexual-assaults-are-poorly-tracked-and-under-prosecuted

[…] TW: this post contains descriptions of rape. Although I focus on the abuse of women in heterosexual marriage, intimate partner sexual violence can happen to people of all genders. Resources are listed at the end of the post. Read part 1 here. […]

[…] The Body is Political: Part 1 (Intimate Partner Physical Abuse) […]