CW: This post discusses experiences with sexual assault and abuse.

Four years ago, I watched the start of the viral hashtag MeToo on Twitter. At first, it was a trickle, and then a flood of people, mostly women, tweeting about their experiences with sexual assault. The hashtag was soon all over the internet, and it led to action and advocacy off-screen. It brought the necessary momentum to hold some perpetrators accountable for their actions and give a voice to some survivors.

It didn’t happen all at once—it took years—but #MeToo gave me the language to understand and talk about my own experiences with sexual assault.

As a girl raised in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, I was given a lot of rules around my body and sexuality. Rules on modesty, dating, and chastity. Rules that told me that the existence of my body could be a stumbling block—even walking pornography—to the boys and men around me if I wasn’t careful. Rules that were sometimes vague or confusing (no leader was even clear on the definition of “petting”), and at other times inappropriately explicit (like when one of my bishops at BYU would go into detail about ways that girls masturbated).

But for all the rules, there was little to no talk of consent. There was no talk of grooming, manipulation, or abuse. And there was little sense that I had an immutable worth as a person and daughter of God.

I had my first kiss at a Pop Warner football game when I was twelve years old. It was a fairly simple, chaste kiss with a boy from school. I went home that night with stars in my eyes, thrilled at the experience. The next day in Young Women’s at church, the Beehives (ages 12-13) were combined with the Laurels (ages 16-18). The teacher handed out bookmarks resembling dollar bills with a message about how our kisses are like currency, and the more we give, the less they (and we) are worth. We needed to conserve our kisses so that they (and we) would be worth something to our future husbands. I went home and sobbed for hours. I knew I would not marry that boy, and I knew that I was now worth less (worthless?), and there was no way to reclaim that spent worth.

I knew and loved this leader. I believe she was doing her best with the messages that she had internalized. But this was the first of many lessons that taught me that the Atonement of Jesus Christ was not powerful enough to cover the romantic or sexual experiences of women, consensual or not, sinful or not.

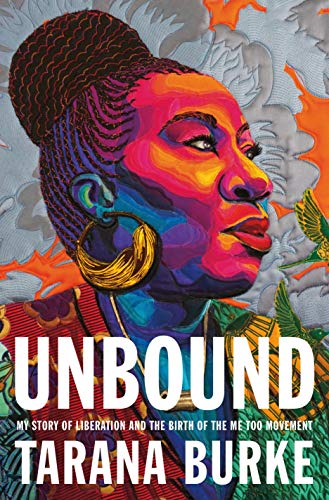

Fast forward to 2017, and #MeToo began trending—a phrase that Tarana Burke had been using for decades in her work as an advocate and activist in creating empathy around experiences of sexual assault. Burke works at the intersection of sexual violence and racial justice, creating movements to bring resources, education, and support for impacted communities. “Me Too” was a way that Burke created space for the mostly black and brown girls in her leadership workshops to talk about the violence in their lives. Her new memoir, Unbound: My Story of Liberation and the Birth of the Me Too Movement, is the breathtaking, heart-wrenching, unflinchingly honest story of her experiences that brought her to this work.

When Burke shares her first experience of being sexually assaulted at age seven, she talks about her fear of being in trouble for all the rules she had broken in the process of her assault—such as “never go off without permission” and “never let anyone touch your private parts.” She was a child and none of this was consensual, but for all the rules she had been given, she hadn’t been taught that if something did happen to her, she was not to blame. Because she interpreted herself to have broken rules in the process of her assault, she believed she was responsible for her abuse. It took many years to consider herself a victim, let alone a survivor, of sexual assault.

I can’t say how many times I had to pause and take a breath while listening to Unbound. Times I had to go back and listen again. Times I wished I had heard these words when I was younger. Like Burke, I was given rules. I did not have an understanding of consent. I did not have a sense of my immutable worth.

Like most women, I have many experiences with sexual harassment. But when I was eighteen years old, I was sexually assaulted on multiple occasions by a boyfriend. Because it was not what I would consider rape, I didn’t have the language to talk about my experiences. And because I was a BYU student, I felt unable to report my assault. At the time, if a student reported sexual assault and had broken ANY Honor Code rules in the process, the student could face school and/or church discipline for reporting. For many years, I didn’t tell anyone what I experienced.

#MeToo gave me the language to understand what had happened to me. When in 2020 I started meeting with a therapist, I was finally ready to talk. I first told a close friend, then my therapist, and then my husband. Over months, I told more friends and family members. And the relief that this brought me is hard to understate. I had suffered from the shame and trauma of my assault for fourteen years. But in the months that followed talking about my experience, I felt healing that I didn’t know was possible. After fourteen years, the flashbacks finally stopped. I felt more at home in my body, mind, and spirit. I felt more able to reclaim the immutable worth that had always been mine but had been blocked from me.

The #MeToo movement gave me the language and space to talk about my experiences and work towards healing. But too many survivors of assault do not have the freedom that the movement extended to me and others like me. Burke talks about how as the hashtag flooded the internet, the voices were disproportionately white, cishet women. Too many people of color and LGBTQIA+ individuals do not yet have the support or resources to share their stories. And too often, Nice White Parents work to keep out the educational resources from schools that will give the language and tools for prevention and healing.

It is not enough to give rules to our children and youth. They need education, a robust understanding of consent, and the safety and empathy necessary to talk about abuse and shame to build the resilience necessary to move forward.

For me, the language I gained from the #MeToo movement was liberating. I don’t think that every survivor needs to share the details of their abuse on the internet. But I hope that Burke’s words reach as many people as possible and continue to free those who are not yet free to move out from under shame and into joy.

12 Responses

So poignant. Thank you!

I can not love this enough!

I have voiced my concern several times on a stake level that we do a lot to protect leaders from being accused of abusing . . . but nothing to help the youth understand consent, assault and how to get help if they need it!

Love this.

I wonder how many sexual assault survivors have “confessed” the the sexual assault they suffered from as a victim to a Bishop??? Trauma upon trauma. Assault upon assault.

Well, I’m one. Thought it was my fault based on what I was taught in YW. I gasped when I read Katie’s story. Swap boyfriend with 40-something year old boss and it’s my story including the part about not telling anyone for fourteen years and finally dealing with it all in therapy. Language is liberating exactly as Katie said. It’s what helped me finally understand what happened.

Elisa this is SO TRUE! Exponential undeserved confessions. My daughter confessed as a teen and then came home and the next day said, ” Mommy, I was rather forced into it. That was not the half of it, the SA turned out to have been a long term predator, despite being 17 years old, of younger relatives and girls, as well as the grooming of the mothers with his charm whilst committing other grooming behaviors. His MOM knew he was after girls and when we filed against him with the police, he and his mommy and daddy, ( his daddy a prominent clergy leader) waltzed into the police station acting like my daughter was the one in the wrong. Abusers are usually always believed and the victims throw away that is what I have experienced during the entirety of my life. I am grateful for the fact that the one time, when I was a very young woman, I reported to a clery leader something that a siblings had done to me, he was wonderful telling me that I was in no way at fault, that this sin was the siblings that I was younger and sinned against. NO, I never saw anything happen to that sibling, however, I was given a faith in myself that has helped me to overcome and try to hang onto self worth through the repeated abuses, denials, and punishment by them and those that they use to cover up with and for them.

Katie, this is such a powerful post. Thank you for sharing your story. Thank goodness for the #MeToo movement and the way it liberated us and gave us the language to talk about our stories of assault.

I find myself outraged at so many of the things you experienced:

As a parent of a 12-year old daughter, I find it appalling that that teacher told you your kisses were like currency and you devalue yourself by kissing. You are so right. Rules are not enough. I’m newly determined to talk to our YW leaders before our next chastity lessons. Consent and immutable worth should be the focus of that lesson.

I’m also outraged at the BYU Honor Code that prevented you and thousands of other students from reporting assaults for fear of being punished. Something is deeply, deeply wrong systemically at BYU if (usually) male sexual assault perpetrators are getting away with violence because the Honor Code effectively silences (usually) female victims. I’m not a BYU person, but I think (?) some things have changed in the last couple of years on that score? What are your thoughts about those changes at BYU?

Anyway, thanks again for this important, vulnerable post. It feels like a gift to read it. And I’m also so glad to know about Burke’s book.

Thank you, Caroline. I was impressed at the response of President Worthen back in 2017-2019 in conducting a large survey of students and alumni’s experiences with sexual assault and reporting and making changes with the relationship between Title IX and the Honor Code Office. I don’t have a clear idea of what has been done to clean up the relationship of BYU police and Provo police in regards to Honor Code violations, because that was part of the problem, too. But I was glad to see BYU make the changes that they did. However, I don’t know if it is enough for the students to actually feel safe reporting. Another level of the problem that I haven’t seen addressed is that bishops aren’t given good training on recognizing consent, assault, grooming, etc. I’ve heard many stories of women reporting assault to their bishops and being told they must repent for their own assaults. And then these bishops are responsible for ecclesiastical endorsements. There is just so much room for ignorance or abuse in this system and almost no recourse for students who are caught in a situation with a bad bishop. It’s very tough.

I hope your daughter’s leaders are receptive to you!

Katie this should be required reading for all youth leaders. So so powerful.

Thank you for writing this

The fact that consent is not taught as an integral part of chastity is one reason why I do not feel good about having my children sit through the chastity lessons I sat through growing up. Thank for sharing your story and carefully illustrating how we, in the LDS community, need to change our messaging around sexual purity.

Thank you for this. I still don’t have the language to talk about my grooming still often feel like it was somehow somewhat my fault (shame, embarrassment, etc.) for “allowing” it to happen and for not having the language of consent nor feeling powerful enough. The church does real damage to women with explicit and implicit rules and expectations around sexuality and relationships.

Thanks for posting this, Katie. I’m so sorry that you were taught such damaging and shaming ideas when you were so young. It’s so sad that these ideas are so very common in the Church. And I’m sorry that you were both assaulted and then put in an impossible situation at BYU, where you feared that you would be expelled for having been victimized.

I’m glad that there’s been some progress, and that you’ve been able to put language to your experiences and what was wrong about them. I was thinking about how far we have to go when I saw this post on Reddit today, where a (young?) LDS woman was sexually assaulted and then questioned herself for having been wearing running shorts. It’s infuriating that our blame-the-victim approach is so alive and well.

https://www.reddit.com/r/mormon/comments/qtamh8/is_it_sin/