Four Decades

I’m turning 40. I am glad I will be 40, especially when I consider that the only other alternative for me at this point would be death. Still, it can be hard to celebrate getting older in a culture that worships youth.

I cringe when my own mother, who has always been a very beautiful woman, makes self-deprecating jokes about how ugly she believes she is now that she is older. Never quite as beautiful to begin with, I had to develop self-esteem that wasn’t entirely dependent on my appearance. I had hoped this would give me a bit of an edge in overcoming my culture’s unhealthy attitudes toward aging. And yet, in spite of myself, my heart sinks when I find a gray hair. My own photographs repulse me because of the wrinkles. It’s not just that my body isn’t as pretty now that I’m nearly 40; it’s less functional! I resent that I have to take two pills everyday to do what my body used to accomplish on its own.

But one nice thing about being a little older is that I have witnessed more history. I only remember glimpses of the seventies—memory pictures taken from very low to the ground, around my parents’ bell-bottoms—but I remember the eighties. Many of these memories are rather kid-centric, like cabbage patch dolls, but I also remember the Cold War and the fall of the Berlin Wall.

But one nice thing about being a little older is that I have witnessed more history. I only remember glimpses of the seventies—memory pictures taken from very low to the ground, around my parents’ bell-bottoms—but I remember the eighties. Many of these memories are rather kid-centric, like cabbage patch dolls, but I also remember the Cold War and the fall of the Berlin Wall.

The war on drugs made quite an impression on me as an elementary school student in the eighties. Over and over again, we practiced saying “No” to drugs. These practice sessions turned out to be the only times I ever said “No” to drugs because no one ever offered me any. If anyone was using drugs in my predominantly Mormon, middle class neighborhood, I certainly never saw any evidence of it.

It was in 1986 that the space shuttle Challenger, carrying “the first schoolteacher in space,” blew up shortly after taking off, traumatizing millions of elementary school students like me watching the lift-off at school. During the walk home, my friends and I tried to make sense of it, making plans for how we would stop things from ever going so horrifically wrong when we were grown-ups. TV hero Punky Brewster did an episode about processing the Challenger disaster soon after, and somehow, it helped to know that children across the nation were working through this together, even the fictional ones.

My parents bought a bulky projector and a videodisk player in the early eighties. Local teens spared our house when they toilet papered the neighborhood because my parents used to let them borrow the home theater, a room above the garage furnished with bean bags. Soon, those record-like videodisks were replaced by rectangular VHS tapes, and then it was back to circles—smaller ones this time—with DVDs.

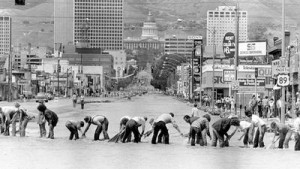

In 1983, an unusually wet winter and spring led to a massive flood in Salt Lake City over Memorial Day weekend. It was probably a devastating and dangerous event, but to my seven-year-old self, the flood was a great adventure. I was delighted to see State Street transformed into a river overnight, the buildings on either side protected by walls of sandbags erected with miraculous speed by my dad, my neighbors, and thousands of strangers, an army of volunteers working together to save the city.

The floods of 1983 were far, far in the past when, in my early thirties, I xeriscaped my first yard. My husband and I spent many hours at the local Water Conservancy District demonstration garden. The elderly head gardener liked working with younger people like us, who had grown up learning about saving the earth. To many people his age, he said, native plants looked like weeds.

But in many ways, the earth-friendly, pro-recycling movement of my generation was simply recycling previously forgotten values. My grandma was amused when Salt Lake City finally installed a mass transit system in 1999. “They used to have trolleys all over the city,” she told me. “You could go anywhere for a nickel. And then they tore them all out to make the roads wider! I don’t know what they thought they were accomplishing. And now, here they are, putting in trolleys again.”

By 2002, years of drought conditions lowered the Great Salt Lake until the Spiral Jetty returned to view after decades immersed underwater. Although I lived near the lake, I was introduced to the Spiral Jetty by my high school and college art text books; it had never been visible during my lifetime. My newlywed husband and I set off to see it a few days after the news broke that it had reappeared. The pilgrimage was none too easy a feat since there was no road at the time, and we had to follow directions like, “Turn right at the abandoned car” and “Turn left at the third cow grid.” When we finally found it, I was surprised. It didn’t look like the black spiral I had seen in those text book photos. Time had changed it. White salt crystals had all grown all over it. It was beautiful; more so than it had been decades before.

By 2002, years of drought conditions lowered the Great Salt Lake until the Spiral Jetty returned to view after decades immersed underwater. Although I lived near the lake, I was introduced to the Spiral Jetty by my high school and college art text books; it had never been visible during my lifetime. My newlywed husband and I set off to see it a few days after the news broke that it had reappeared. The pilgrimage was none too easy a feat since there was no road at the time, and we had to follow directions like, “Turn right at the abandoned car” and “Turn left at the third cow grid.” When we finally found it, I was surprised. It didn’t look like the black spiral I had seen in those text book photos. Time had changed it. White salt crystals had all grown all over it. It was beautiful; more so than it had been decades before.

When I was in high school, my best friend asked my parents if I could go with her on a 13-day tour of Western Europe. My group of teenaged travelers from Utah was combined with a group from Kentucky and another from Texas. The Texas group was an odd bunch, ignoring castles and cathedrals to shop at every Benetton clothing store and saying strange things about how Europe made them appreciate America. Europe made me appreciate Europe. And time itself. Growing up in suburban Salt Lake City, most things around me were new, and many of these new things weren’t very nice to look at: big box stores, cookie cutter housing, strip malls.

When I returned, I painted a picture of a medieval bridge I had walked across in Lucerne. A few months later, recognizing the bridge from my painting, my mom called me when she saw on the news that it was burning down. It survived thousands of years, but not forever.

When I returned, I painted a picture of a medieval bridge I had walked across in Lucerne. A few months later, recognizing the bridge from my painting, my mom called me when she saw on the news that it was burning down. It survived thousands of years, but not forever.

That same friend who traveled with me to Europe during our teens invited me to join her on a business trip in Europe about a decade later. After we arrived, she warned me that her last several travel companions had gotten married shortly after returning from their trip; it was some sort of charm—or curse—depending on your point of view. I wasn’t at risk, I told her. I wasn’t seeing anyone. I didn’t know it then, but just the week before, I had gone on a first date with the man I would marry.

My family unluckily happened to be on a family vacation in Los Angeles in 1992 when three days of rioting destroyed much of the city and killed dozens of people. A reporter asked me, my parents and my four younger siblings to gather together in front of a camera, then proceeded to interview my father—and only my father. I was mildly indignant when I realized that the rest of us had been posed for our cute faces, not because anyone had any interest in our thoughts. At age 16, I felt like I had something to say about this frightening aspect of our society that I was witnessing up close for the first time. Looking back, I wonder what it possibly could have been, since such violence renders me speechless today.

When I was a child, some adults in my Mormon community would speculate that the “end of days” might come with the beginning of the next millennium. I had enough faith to believe it possible, enough credulity to doubt it, and a great deal of hope that it wouldn’t happen, even though the grown-ups seemed to be looking forward to it so much. Having the world as we know it end when I had barely reached adulthood, before I had any time to live my own life, hardly seemed like a pleasant outcome to me.

As the year 2000 approached, the speculation all but dwindled away. It is one thing to anticipate an apocalypse within a few decades, quite another to believe such a thing could happen any time soon. Without an apocalypse to look forward to, we all needed some sort of disaster to get excited about, so we settled for Y2K. It was just a computer glitch, and a disappointingly easy-to-remedy computer glitch at that, but it was something. During the year 2000, I went to Washington D.C. to intern for the senator who chaired the Senate Special Committee on the Year 2000 Problem. By that time, it wasn’t such a problem anymore.

I loved working at the Capitol. I reveled in the politics and the history. I was changing the world! My idealism amused a friend who had spent more time in D.C. than I had. He assured me that someday I’d be as jaded as everyone else.

About a year later, the world did end—at least, the world as I had known it. I had grown up in a country that appeared to be invincible. A place where, even when we were at war, the wars were always far away. Early in the morning on September 11, 2001, I sat in my graduate-level government economics classroom. Our professor asked if we should hold class. Should we continue as planned, in defiance of terrorists that wanted our nation to come to a stop? Or did we need to take a break to mourn and show respect for the dead? This usually loud, opinionated group sat in silence, many with tears streaming down their faces, and gave no answer.

I was back in D.C. just recently. There were new plaques on the walls, new facts added to the tours, about how this great city, the symbol of our democracy, had been built by slaves—just like the monuments of ancient tyrannies. It was less ideal but more true.

For awhile, everyone was fussing and fretting about my generation, the Generation X-ers. They have since lost interest and now I can be equally confused by Millennials. I feel so mature, wringing my hands at the nonsense of the younger generation.

Millennials have lived their whole lives with access to the Internet. I would guess this makes them quite smart. Before the Internet, when I didn’t know something, I was stuck wading in my own ignorance until I got to a library building, or more likely, forgot the question. There was no Google fairy godmother to grant instant knowledge.

My first semester of my sophomore year was my last without Internet access. That was when I had to write the paper my roommates affectionately referred to as the Paper from Hell. I had to contrast Dante’s description of Hell in the Inferno to 13th-century Christian theology, using only resources I could find in print in that small Idaho town. It seemed that the evolution of medieval Hell theology was not an extremely popular reading topic among potato farmers. I ordered many books and articles through interlibrary loan, waiting patiently for them to arrive only to find that they usually had none of the information I needed.

My sister forced me into the cell phone age by gifting me a flip phone. She didn’t like that she had to show up on time at a designated meeting place old-school style to successfully find me. I was slow on the uptake when social media became a thing, too. I was working at my first post-grad school job and hearing that social media was the best new way to do health education, even though sitting at a computer and telling people to exercise sounded ridiculous. “Doesn’t Twitter mean more messages? I hate checking my messages,” I told a coworker. The first time I logged on to Facebook, I found that Facebook already knew me. There were tagged photos of me in there; I already had Facebook friends waiting. Going forward, I did use social media for work, for play, and for no good reason at all. I love my iphone even more than I loved the blackberry that preceded it.

Just as computers and cell phones were taking over America, I spent a year and a half without them as a missionary in a country without infrastructure for that sort of thing. One day I stepped outside to find a crowd of people pointing at the sky. A solar eclipse was happening! Right at that moment! And the news of this event, which could be forecasted hundreds of years in advance, had taken me by surprise.

In spite of the lack of technology, no one was surprised by the hurricane. Our mission president announced that a hurricane would strike in two days at noon. It seemed odd to me that a disaster could be scheduled so neatly, to the hour. By the time we left the meeting, people were outside spreading the word to their neighbors, yelling, “¡Viene ciclón!” at the top of their lungs, taping up windows and stocking rice and beans. On the scheduled disaster day, I gathered with other missionaries at one of the few apartments with a telephone to wait out the storm. The mission president called that morning to make sure we were ready—and to let us know that the hurricane had been rescheduled for 2:00 in the afternoon. At about a quarter to two, he called again and asked me how I liked the hurricane. I said I wasn’t impressed. As if to retaliate for this cavalier dismissal, the hurricane arrived in all of its glory just as I hung up the phone. Across the street, a roof peeled off of its building. Palm trees, still upright, walked away from their roots and down the flooded street, and water spilled into the second-story apartment.

A few weeks later, we bought t-shirts from a local entrepreneur that said I survived Georges. “It doesn’t seem like something we should brag about, when so many people didn’t,” one of my missionary friends pointed out. We hid our t-shirts in our suitcases instead of wearing them.

A few weeks later, we bought t-shirts from a local entrepreneur that said I survived Georges. “It doesn’t seem like something we should brag about, when so many people didn’t,” one of my missionary friends pointed out. We hid our t-shirts in our suitcases instead of wearing them.

If fate doesn’t intervene, I can expect to live out as many years into the future as I have already lived in the past: four more decades. I won’t spend two of those decades growing up or one of those giving birth—projects that dominated three of my first four decades. While time always feels scarce, I anticipate that I will have even more of it to enjoy all the other experiences that life has to offer than I have had in the past.

I have the advantage of perspective, now that I am a little older. I see that things change, that I change. History itself changes, not sitting so solidly in the past as one would expect. I also see that too many things stay exasperatingly, devastatingly the same. I see through the eyes I have now, but it is not so difficult to remember how I used to see when I was more innocent, more ignorant, less mature, and less opinionated. If I channel it correctly, this wider perspective could make me a more empathetic person during my next forty years.

One of my heroes from history, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, once said, “We shall not be in our prime before fifty, and after that we shall be good for twenty years at least.”

I have time.

Four Decades

6 Responses

i enjoyed your road trip through the past thirty or so years very much! I’m with Ms. Stanton. I’m well into my prime (66 years and counting!). Enjoy the next twenty six years!!

After working at my local Arts Council for many years, I discovered an important trend. The interesting art showing high levels of technical skill and sophistication was being produced by women over 30. The REALLY interesting art was being produced by women over 60. We 40 somethings have got plenty of time. Pay attention to it! 🙂

I loved reading this, April! It was like looking back on my own life, just changing the countries and experiences a little. I wonder what future decades will bring for all of us.

A fun read! Happy 40th, friend!

I loved reading your reflections here, April.

This was so nice to read. So much wisdom and observation in those 40 years.