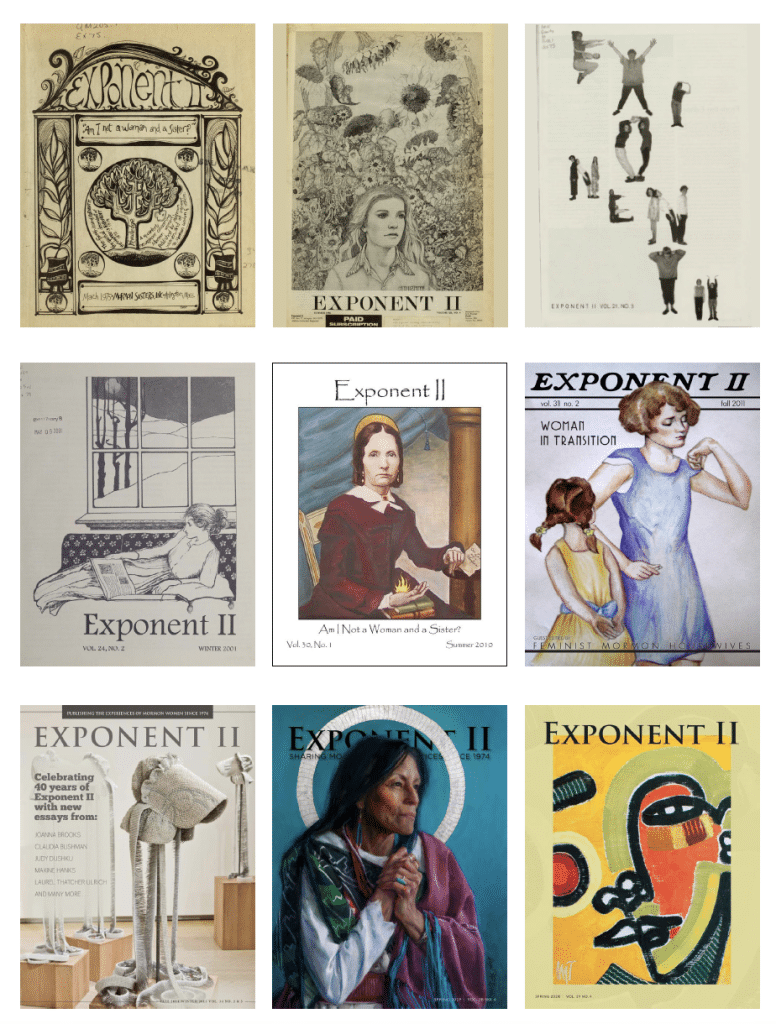

One of the original projects of Exponent II was to create a usable past for Mormon women, which was not available to Mormon feminists in the 1970s. Historian Michelle Moravec noted that many different kinds of feminist groups held this goal at that time. The front page of the first issue (Vol. 1 No. 1, 1974) introduced readers to Woman’s Exponent, published in Utah between 1872 and 1914, connected the work of Exponent II to the groundbreaking historical work of Juanita Brooks, and summarized the activities from an earlier retreat in Western Massachusetts. These three activities were at the forefront of this broader project: education about first-wave Mormon feminists and their writing, connecting readers to historical research on Mormonism, and building feminist community and shared knowledge within The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. While Exponent II is most famous for its reflective writing on the lives of Mormon women, the art of Exponent II has always played a significant role in the publication, serving to illustrate, decorate, and celebrate Mormon women’s stories while critiquing patriarchal norms. The starting question for this discussion is: what was (and is) the function of the art, illustration, and photography in Exponent II? What did it mean to the artists and art editors, and what might it have meant to readers?

Many of the illustrations in the earliest issues of Exponent II appear to be purely decorative images of women from the past. In the 1970s, Joyce Pollard Campbell, Carolyn Durham Peters (later Person), Bonnie M. Wood, and Linda Hoffman Kimball served as art editors and illustrators, with additional artists offering their work for publication. They created images specifically for Exponent II but also drew from books of copyright-free images. Among the illustrations were drawings of children and women from the past engaging in domestic life. Founding Mother Laurel Thatcher Ulrich observed that “Spunky illustrations by local artist Carolyn Durham Peters (later Carolyn Person) captured our wrenching discussions better than any of the essays in the volume.” To the contemporary feminist viewer, though, the connection between such images and the text is not always obvious, as many of the illustrations emphasized a domestic innocence and idealism that appeared to be at odds with the complex storytelling around the lives of Mormon women. In contrast with these narratives, the illustrations can seem deceptively reductive.

While the Exponent II is most famous for its reflective writing on the lives of Mormon women, the art of Exponent II has always played a significant role in the publication

Feminist art historian Kimberly Rhodes shed light on the ways in which feminist artists in the 1970s used images of Victorian women to set up critiques of traditional gender roles. Such neo-Victorian representations of women were central to artists’ commentaries on women’s roles in society. In the many neo-Victorian illustrations of Exponent II through the early 1980s, Mormon feminist artists employed representations of women’s dress and domestic roles in the 19th century. These images offered an important counterpoint to the texts that they illustrated and enriched the storytelling by offering additional points of connection and commentary. This is not new to Exponent II, as illustrators from the Middle Ages onward have understood that illustration had the power to offer an extended commentary on the text.

An example of this kind of neo-Victorian illustration is in the figure of two upper class women standing in a formal drawing room and talking with each other with no caption (Vol. 1 No. 4, 1974, pg. 11). This illustration was on the same page as two other articles: a short fictional story of a young mother receiving two unexpected and judgmental visiting teachers while in her bathrobe and a short article on a Mormon woman being elected to the town council in New Castle, New York. The lower right corner of the page includes a handwritten quote by suffragette Elizabeth Cady Stanton: “The religious superstitions of women perpetuate their bondage more than all other adverse influences.” The short story was not set in a Victorian past, but the neo-Victorian illustration of the two proper-looking women created an association between the two figures and the two judgmental visiting teachers. The Elizabeth Cady Stanton quote emphasized the ways in which ideas about the proper role of upper class women held these women in bondage to their supposedly high station in life. The article about the Mormon woman elected to the town council demonstrated alternative public roles that Mormon women were finding in their lives. Where other art editors might have chosen to illustrate the young mother in her bathrobe, Exponent II art editors visualized tensions between present realities and religious ideals through the use of neo-Victorian imagery. The illustration of the two Victorian women tied the various contents of the page together and created additional layers of commentary on the written content.

The first issue (Vol. 1 No. 1, 1974) used the tagline, “Am I not a woman and a sister?” and for the cover of the second issue (Vol. 1 No. 2, 1974), Carolyn Peters (Person) illustrated that phrase. She appropriated an Abolitionist medal made by Wedgewood artist William Hackwood, c. 1786. Hackwood’s medal asked, “Am I not a man and a brother?” and showed an enslaved Black man in profile and kneeling on one knee with chains on his wrists and ankles. This image and its tagline, also adapted for enslaved women, were used throughout the duration of the Abolitionist movement to draw attention to the oppressions of slavery. Carolyn’s version showed a discreetly bare-chested white woman kneeling in the same position, with hands raised and pleading, and chains attached to one ankle. While today we might question the validity of white women appropriating an image of an enslaved Black man, Carolyn’s critique of women’s limited power within the LDS Church was a very strong one. In fact, this image levied the harshest assessment of the LDS Church in relation to its women of all of the content in the early issues of Exponent II. Here, the cover image ventured into a kind of commentary that went beyond the limits of the articles. The cover image conveyed a kind of pain, objectification, and relationship with the Church that was difficult to state in words while trying to keep the publication celebratory of a shared identity in Mormon womanhood.

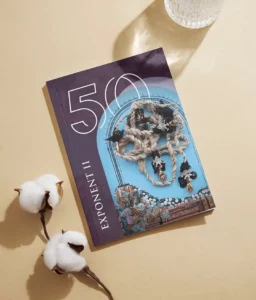

Exponent II was strongly associated with Boston-area Mormon feminists, but there were a number of guest-edited issues by groups of Mormon feminist readers in other places. The cover images and illustrations of the first ten years or so of the newsletter emphasize these different locations. One early issue included drawings of architectural details of the Brigham City Utah Tabernacle and the Memorial Church at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts (Vol. 1 No. 2, 1974). The cover of another issue shows a historic water tower in Chicago, Illinois, that survived the 1871 fire (Vol. 7 No. 1, 1980). The Kirtland, Ohio, readers guest edited an issue (Vol. 7 No. 4, 1981) with a picture of the Kirtland Temple on the cover. Together with identifying the locations of different contributors, there is a strong sense that the art editors and the editorial board wanted to emphasize the many places where their readers and contributors lived. This was important, as myths about a limited New England readership persisted for decades. The Sue Paxman Collection (MSS 6192) held in BYU Library’s Special Collections holds the evidence against this particular fiction, with seven different subscriber lists. One single list (undated, likely from the 1980s), included about 4,300 subscribers, with the two most common addresses being in Salt Lake City and Provo, Utah. Beyond that, there are an additional 800 cities listed, including all 50 states and 14 countries. In the 1980s, this was an impressive reach for a newsletter.

Through the early 1980s, there was an expansion in the numbers of women who identified as illustrators and art editors for Exponent II. Renee Tietjen, Linda Hoffman Kimball, Jan L. Braithwaite, and Eileen P. Lambert, among others, all shared in the work of creating and editing art for the newsletter. By the late 1980s, there were a few examples of art photography in the newsletter, like Zina Nibley Peterson’s “Quiet Lights” (Vol. 13 No. 4, 1987, p. 8). In the following years, there are far fewer illustrations compared with earlier. In these years, the editorial team created themed issues centered on heavy issues, like teenage drug use (Vol. 15 No. 2, 1989) and abortion (Vol. 15 No. 4, 1990). Perhaps it seemed best to leave out illustrations, which may have been interpreted as making light of difficult topics.

Issues from the 1990s and 2000s emphasized photos and contained fewer illustrations. Eileen Perry Lambert remained involved as art editor, and Deborah Sirotkin Butler was a regular illustrator through the early 1990s, together with others. Photos tended to be of article authors, with or without their families, and pictures from Exponent gatherings, which gave readers a sense of the writers as real women they could connect with and possibly meet at a retreat. These visual connections to community members may have been particularly important for strengthening Mormon feminist networks in the wake of the public excommunications of Mormon feminists and other scholars in September 1993.

The newsletter turned into a magazine in 1997, at which point the role of art editor went away, but the role of design editor emerged and was filled by Kate Holbrook. Some issues showcase examples of contemporary Mormon feminist artists and their work, such as the interview and work of Fae Ellsworth (Vol. 22 No. 1, 1998). In the 2000s, Lena Dibble and Linda Hoffman Kimball are regularly listed as artists, with occasional contributions by others. Themed issues tackling heavy topics, like the one on “pornography addiction” (Vol. 28 No. 4, 2008), contain no images other than the cover photo.

In 2010, art re-emerged as an important element of the magazine with Margaret Olsen Hemming as the design editor. She later became the art editor (2012-2015) and then the editor of the magazine (2016-2021). She sought out contemporary Mormon feminist visual artists working in a variety of media and particularly worked to include women artists of color. During her tenure, she turned the publication from one that used images in limited ways to one that understood the power of images to strengthen the written content, which has continued under the art editorship of Page Turner and Rocio Vasquez-Cisneros. Today, art images often fill the page and complement the themes of the adjacent articles. Artist statements often accompany art and suggest ways for readers to interpret the contemporary work, which is often abstract in nature. These statements facilitate meaning-making for readers, who can then draw their own connections between art and article. Though the art images of the present look much different than the early neo-Victorian illustrations from the 1970s, art once again serves a strong commentary and content role.

In September 2021, I spoke with Page Turner — long-standing Exponent II Art Editor and now Art Community Ambassador — about the ways in which contemporary Mormon feminist artists find a degree of safety in abstraction, which can hide the sharper edges of religious critique in shapes and colors and create a greater freedom of expression. This work stands in sharp contrast to the many Mormon men who paint recognizable religious subjects in more concrete, realistic ways, taking cues from the Renaissance and lacking spiritual depth. So much contemporary artwork in Exponent II is filled with an attractive vitality that realizes a spiritual imagination in the ordinary situations and objects of people’s lives. Let’s never lose that.

NOTES:

Moravec, Michelle. “Fictive Families of History Makers: Historicity at the Los Angeles Woman’s Building. In Meg Lindon, Sue Maberry, and Elizabeth Pulsinelli (eds.), Doin’ It in Public: Feminism and Art at the Woman’s Building. Los Angeles: Otis College of Art and Design, 66–93.

Rhodes, Kimberly. “Archetypes and Icons: Materializing Victorian Womanhood in 1970s Feminist Art.” Neo-Victorian Studies 6, no. 2 (2013): 152–180.

Ulrich, Laurel Thatcher. “Mormon Women in the History of Second-wave Feminism.” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 43, no. 2 (2010): 45–63.

Nancy is a professor at Utah Tech University, where she has taught for 17 years. As a long-time Exponent II blogger, she currently serves as the blog representative on the board.

St. George, Utah