The timing of this book review is in recognition of New Zealand’s annual Waitangi Day on 6 February. Waitangi Day, in summarised and abridged terms, is in celebration of the signing of New Zealand’s Founding document, The Treaty of Waitangi. This document was written in both Māori and English, and was signed by over 500 Māori chiefs as well as British Government officials in 1840. It is a broad declaration of standards between the Māori and British to unitedly construct and a government in New Zealand. Because it was written in both languages, important and imperfectly translated nuances have been an ongoing source of debate. Though it is celebrated as the day the nation of New Zealand was born, The Waitangi Treaty continues to be a source of parliamentary debates in New Zealand Parliament from the time of its initial signing until today.

Likewise, church history is often viewed through the lens of the US church leaders and record keepers, turning the nuances of local conversion and cultural application into footnotes when not completely ignored or obliterated. Recent groups like International Mormon Studies have sought to encourage, develop and analyse local histories of the church in a manner that is interwoven with cultural and nationalistic perspective, celebrating Mormon thought, research and historiography through an international point of view. In this sense, Turning the Hearts of the Children is one of the most important contributions of nationalistic content within a Mormon context to date.

Likewise, church history is often viewed through the lens of the US church leaders and record keepers, turning the nuances of local conversion and cultural application into footnotes when not completely ignored or obliterated. Recent groups like International Mormon Studies have sought to encourage, develop and analyse local histories of the church in a manner that is interwoven with cultural and nationalistic perspective, celebrating Mormon thought, research and historiography through an international point of view. In this sense, Turning the Hearts of the Children is one of the most important contributions of nationalistic content within a Mormon context to date.

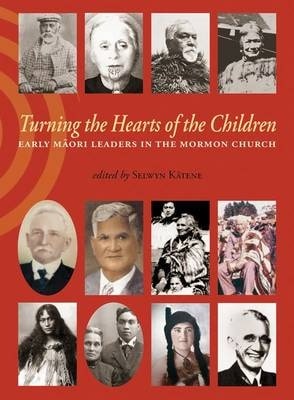

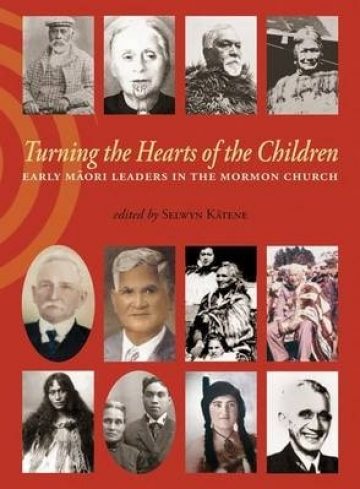

The book is an anthology edited by Selwyn Kātene. Kātene wrote the introduction, inclusive of a brief history of the development of the church in New Zealand, and positions the book in terms to illustrate and honour the testimony of the Māori within a Mormon context. An interesting observation of his is in describing the religious position of the Māori in comparison to other Christian religions introduced in New Zealand previous to the Mormons. Kātene points out that native Māori belief, tribal structure and spiritual practice better suited the theism taught by the Mormons in comparison to the Church of England and other European religions, making a distinction that is important in the study of the church as a “world-wide” organization.

Now on to the proper review—

As a woman and a feminist, there are three things that especially delighted me about this book. First was its interwoven use of Māori terms, such as whanau (family), rangatira (chiefs), and kaumātua (respected elders) making this an outstanding example of ways in which organizational and cultural inclusion are equally matched. The use of native Māori terms made this a much more personal telling of the church in New Zealand, using the voice of the people who held and hold the land, lending to a sense of generational testimony. This helps to place the history of the church through its church members in context with Māori culture, tribal governance and perspective.

The second is the chapter dedicated to the church history of Pare Tauwātea Duncan (“Aunt Polly”) that detailed her church callings, but included context withing her family, employment, and patriotic work during World War II. The book includes partial text to a “sermon” offered by Ms. Duncan, as follows:

It is a time-hounored adage that love begets love: Relief Society was given to the daughters of God to help them pursue and attain happiness. […]Visiting the sick and serving the less fortunate kindles a love within the heart which warms and glows, radiating happiness throughout one’s being.

Though little analysis is given to the ideology of women offering sermons, it is clear in this chapter that Māori women were expected to be leaders in more places than the kitchen, and in particular, Ms. Duncan was both a leader and an advocate for women within church ranks. Reading about Polly and her powerful work to progress the gospel made me love her as a sister, in a way that it uncommon, at least for me, in reading typical church materials intended to address the position and role of women.

Third, and the best part of the book — was its overall assumption of women as spiritual leaders. My favourite example was the story of a woman named Raupia, who had seen the missionaries in three separate and distinct visions well before they arrived at her home. The strength of her visions influenced her husband, who believed she had seen the visions. When the missionaries arrived, both she and her husband knew that these were the missionaries that had been revealed to Raupia, consequently resulting in the baptisms of her and her husband. Reading this empowered me and made me wonder how many other Mormon women were privy to visions, and how as a church, we might do better at preserving the spiritual records of women.

This book is more of an antiquarian collection than a historiography. This is both a negative and a positive. It is negative for those who seek more analytical discussion of the church and its effect on and within the Māori culture. Yet it can also be viewed as positive because in its purest sense, this is a resource that can be used as rich reference for future tribal, national and transnational studies of the Mormon influence within the Māori. I was disappointed in its heavy patriarchal emphasis, but as the Māori appear to be a patriarchal society, and as the church is a patriarchal organization, the stories of women are organizationally diminished at both angels through little fault of the chapter authors. Because of this organizational exclusion that was significantly disheartening, it made the inclusion of females in the book all the more significant and sacred.

As a whole, this book is an important and worthy record of the church among the Māori. It includes and impressive collection of images of New Zealand church members in traditional Māori attire. I recommend it for those who are interested in global church culture, Mormon Māori culture and those who are interested in a collection of native LDS conversion stories. It can be purchased internationally with free international shipping through Fishpond as it is not currently available through Amazon.

Kia Ora!

4 Responses

Thanks so much for this review, Spunky, and particularly for pointing out those moments that tell the stories of Maori Mormon women. I suspect that in many cultures, Mormonism’s patriarchal overlay reinforces women’s subordinate societal roles, but that it also opens up/reinforces some spaces for women’s leadership and power. It sounds like something of that dynamic happened in New Zealand. I’m excited to read about these women more in depth in the book!

This is really fascinating, Spunky. I’m so glad to hear that, despite the overarching patriarchy that is inevitably embedded, there were fantastic female stories included as well. What time period does the book cover? Does it cover things like the Church College of New Zealand? Or does it mostly focus on the early history?

It is antiquarian, rather than academically historical, so the Church College is included in reference to the people who knew of it, attended it, and built it. But it is not a history of the college, so the organizational history of the college is absent. Also because it is not a history, it doesn’t cover one period of the Mormon Māoris, the first Māori prophets who foretold of the Mormon missionaries in 1840 are included, and some of the contributions are based on the authors’ personal memories and records, so it could be argued that it “covers” 1840 to the present day. The emphasis of the book is Early Mormon Māori leaders– leaders being both men and women, regardless of callings or even church standing, making this an unusual and important contribution to church antiquarian collections and a prime resource for historians.

I think there are always many women who have visions and prophecies given to them. It is the patriarchal culture that devalues those visions, and hides them away in personal and family histories. I have experienced the fear and limits put on women who are willing to be open about the gifts given to them, by priesthood leaders who don’t also have those gifts. It seems common for men to believe that if they do not have a gift, then a woman couldn’t have that gift, because she lacks the priesthood.