October 29 is the deadline for Exponent II’s annual essay contest. The subject and rules for entry can be found here. We are excited to read your submissions and print them in the Winter 2018 issue of the magazine. The winner will receive a week’s stay at a writers’ retreat in Ireland. The following is an example of the essay contest theme, “Our Spiritual Foremothers.”

When I was twelve years old, my mother took me to see Maya Angelou and Harry Belafonte speak on campus at Michigan State University. At the time, I knew nothing about Maya Angelou except that my mother loved her writing and that her real name was Marguerite, which was the fancier–and therefore better–version of my name, Margaret. I was a nerdy, imaginative girl who loved books with happy endings and still enjoyed princess dresses. At twelve, I desperately wished to be pretty, fun, and carefree enough to be popular with my peers. With no preparation for who she was or what she would say, I imagined that Maya’s fancy name and her career as a writer made her into everything I aspired to be–beautiful, elegant, and adored.

As soon as I heard Maya’s rich, resonant voice, my heart was transformed. For a brief moment, I felt disappointment. She was not the pretty, sweet, soft-spoken girl that I had hoped to admire. In the next moment, I felt that disappointment, as well as the immaturity that underlay it, slide away from me forever. Maya’s voice was extraordinary. I was too young to take in the words she was saying, so I only focused on the timbre and rhythm of how she spoke. The longer I listened, the more I wanted to have a voice like hers. Her confidence and strength undergirded every word. She used complex words and didn’t apologize for them. She laughed often and without self-consciousness. Looking back, I don’t remember the message she shared and I barely remember Harry Belafonte at all. But I remember her sonorous voice changing my understanding of what it meant to be feminine and what kind of voice I aspired to have.

A few years later, I read I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings for the first time. At twelve I was ready for her voice; it took me a few more years to be ready for her words. One of the reasons reading books is important is that it teaches us empathy. In following a story through someone else’s eyes, we are forced outside of our own perspectives and narratives. Maya Angelou’s books and poetry excel at this, not just because she pulls the reader into her perspective with the force of her writing, but because she offers the gift of empathy to the reader. She powerfully claims her space, but also shares compassion and forgiveness. As I read more and more of her work, I realized that I not only aspired to a voice like hers, I also aspired to a soul like hers. I wanted that kind of commitment to justice and unflinching truth-telling.

At the same time, I became aware of the importance of the social space that Maya inhabited, and how different it was from my own. Maya’s background–poor, Black, southern, and abused–looked nothing like mine. It was challenging and humbling to realize that the advantages that I had been given without merit came with a responsibility to seek out the voices that are not being heard. Maya taught me to be unafraid to tell my story but to also to be curious enough about the world to seek out others’ stories. She taught me to make space in my life to take in the struggles of others, and to use my power to amplify their voices. Whenever I reread her words I am reminded to do better.

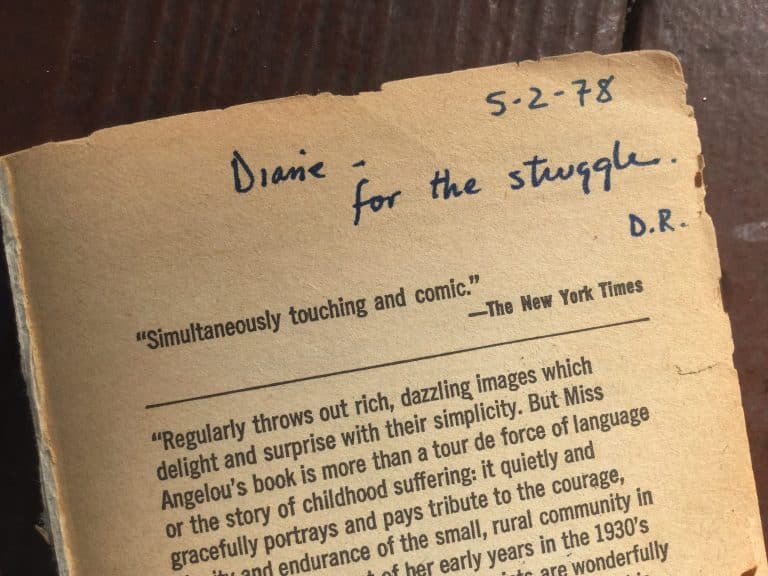

My copy of I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings is well-worn and missing its front cover. I don’t remember where I picked it up, but I know that someone else owned it before me, because written in pen on the first page is,

“5-2-78

Diane–

for the struggle.

D.R.”

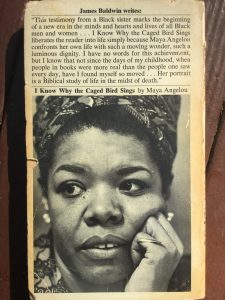

The back cover is mostly a black and white picture of a younger Maya Angelou, looking off to the side and looking like she’s listening but is ready to speak. She is beautiful in a way that my 12-year-old self would never have understood. When I need some wisdom for the struggle, I pull out this book. I wonder who Diane and D.R. were, what they struggled with, and consider how they felt personally connected to the same woman I deeply admire. I like that I carry a tiny piece of their story along with the book. Looking at the photograph of Maya, I recall a dark auditorium, my mother beside me, and a luminous voice simultaneously claiming her space and holding space for others. I imagine Maya saying out loud the words she wrote, “There is no greater agony than bearing an untold story inside of you.” Sometimes that inspires me to speak. Sometimes it reminds me to listen.

The back cover is mostly a black and white picture of a younger Maya Angelou, looking off to the side and looking like she’s listening but is ready to speak. She is beautiful in a way that my 12-year-old self would never have understood. When I need some wisdom for the struggle, I pull out this book. I wonder who Diane and D.R. were, what they struggled with, and consider how they felt personally connected to the same woman I deeply admire. I like that I carry a tiny piece of their story along with the book. Looking at the photograph of Maya, I recall a dark auditorium, my mother beside me, and a luminous voice simultaneously claiming her space and holding space for others. I imagine Maya saying out loud the words she wrote, “There is no greater agony than bearing an untold story inside of you.” Sometimes that inspires me to speak. Sometimes it reminds me to listen.