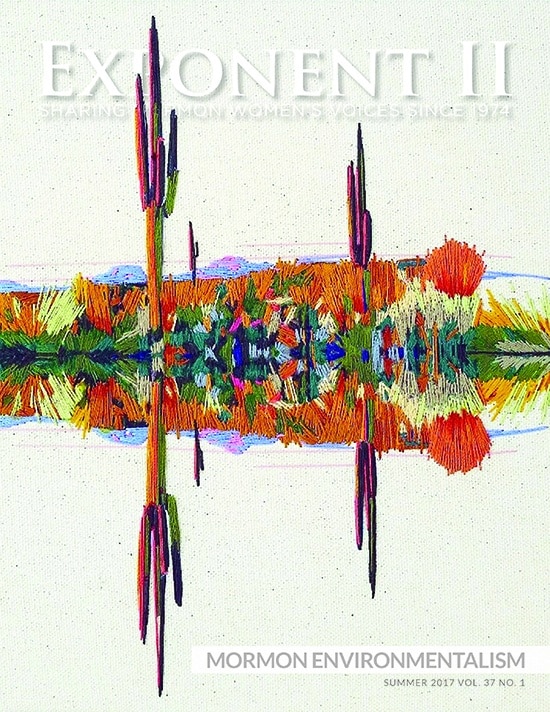

The following is the Letter From the Editor for the Summer 2017 issue of Exponent II, which has a theme of exploring nature and environmentalism. To make sure you receive a copy of this issue, please subscribe here by July 15, 2017. The cover art is by Stephanie Kelly Clark and was made with embroidery floss. You can learn more about her and her work here.

The following is the Letter From the Editor for the Summer 2017 issue of Exponent II, which has a theme of exploring nature and environmentalism. To make sure you receive a copy of this issue, please subscribe here by July 15, 2017. The cover art is by Stephanie Kelly Clark and was made with embroidery floss. You can learn more about her and her work here.

Garden Theology

It’s impossible to approach my home without noticing my garden. The only sunny spot in our woodsy yard is right by the front door, so that’s where our vegetables live. I love that every time I go in or out I get a quick check-in with my plants: right now the sugar snap peas are towering over their trellis, burdened with little white flowers and juicy peas; the tomatoes are putting out their first small fruits; the lettuce and spinach are spilling out of their beds; and the berry bushes are in flower, giving hints of what will come soon. I have a tendency to anthropomorphize my plants, and I speak and sing to them while I work. When I need a place to feel peaceful, I head to my garden.

Surrounding my garden and home are about 300 trees, a chorus of birds, a great deal of moss, and more insects and fungi than I could dream up. Not missing a lawn, every day my children and I find feathers, nests, bits of interesting bark, snail shells, and jewel-toned insects. Right now, the trees are full of bright-green leaves and the chirping of baby birds. When I want to feel joyful, I head to the woods.

Still, I am not unaware of a different side of my garden and the woods. My own experiences have convinced me that “the wild” is well-deserving of its name. My vegetable garden, a liminal space that straddles the man-made and the natural world, is in constant warfare. I have killed countless aphids, slugs, beetles, caterpillars, and various kinds of fungi and weeds. I have even brought in mercenaries in the form of ladybugs and chemical warfare in the case of a particularly aggressive fungus. The more “natural” or organic I want my garden to be, the more violent I have to personally be: a pesticide may kill from a distance and be easier and faster, but it takes a tougher skin to pull caterpillars off my parsley one-by-one and smash them. Paradoxically, the more committed I am to a chemical-free, clean-water, clean-soil garden, the more I have to roll up my sleeves and kill things with my bare hands. The word “organic” no longer leaves me with vaguely positive, fuzzy feelings; I know the hand-to-hand combat that it involves. While I interfere less in the woods, I am not a total bystander to the conflict going on there. I spend countless hours clearing out invasive species, attempting to eradicate entire populations from my property. I also observe the constant struggles between predator and prey, the daily efforts to stay alive at the cost of another living thing.

When I was growing up, my mother often quoted Annie Dillard: “Fish gotta swim and birds gotta fly … insects, it seems, gotta do one horrible thing after another.” After relocating to a home in North Carolina fifteen minutes from where Ms. Dillard lives, last year I decided to reread Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, the source of that quote and many other priceless reflections on nature. In her chapter on insects, she questions whether nature has any particular reverence for life at all, as the vast majority of insects die before reaching maturity. In observing the daily massacres of tiny life, she is skeptical that any greater force is acting on their behalf or caring about the sanctity of life. “If I gathered a cup of ocean water,” she writes, “would I be holding a core of dying and dead barnacle larvae? Should I throw them a chip? What kind of world is this anyway? Why not make fewer barnacle larvae and give them a decent chance? Are we dealing in life, or in death?”

When my time in wildlife was limited to an occasional walk in the woods, I understood Mother Nature as simply soothing, peaceful, and still. However, I have found that the more deeply engaged I am in the environment—the more I am an active participant and not a visitor—the more I realize that Mother Nature is just as capricious and violent as the God of the Old Testament. Death, destruction, and aggression all inhabit a single tree that seems to be quietly sunning itself and showing off its jeweled green leaves. It is simultaneously gentle and lovely, and more violent than we could imagine. Last week, I found the tiny remains of a caterpillar that appeared to have been eaten from the inside out by some kind of wasp or beetle. It looked like it had died in agony. If there truly is a divine spark behind each creation, then the world of insects seems to certainly have been created by the God of the Genesis and Exodus.

I have often wondered why deity seems so different in our various books of scripture: a vengeful and blood-thirsty Old Testament God who orders genocide and a New Testament Messiah of mercy and love for each individual. The stories of the Old Testament often leave me uncomfortable or even horrified. But my time in nature has made me question whether I can take the God of the New Testament while leaving behind the God of the Old. The Old Testament speaks to me primarily of death; the New Testament speaks primarily of life. Nature tells me that the two are inseparable. We are dealing in life and in death, as uncomfortable as that makes me at times.

In the garden, I often choose who lives and who dies. I choose strawberries over slugs, cucumbers over caterpillars, and onions over onion grass. But even that small space exposes me to the limits of my own control. All the tools I possess and work that I do sometimes fail, and I am left to clean up the remnants of a beloved plant. Sometimes the cause is obvious: an overwhelming infestation of beetles, for example. Sometimes it seems to come out of nowhere, and a plant collapses overnight. It is a good lesson on the limits of formation and reminds me of what my friends with adult children tell me: that even the creator cannot keep everything in the order of her preferred design.

In this issue, we explored many different understandings of nature. In “Parable of the Turtles,” Kyra Krakos uses science and demography to critique Church leadership’s claims of a population crisis. Karen Rosenbaum shares a fictional piece about a woman with a complicated relationship with skunks. Kirsten Ward writes of some of the wisdom she’s learned in her work as a biologist in “Lessons from the Bog.” Our features for Women’s Theology and Women’s Work, as well as the personal essay, “Inevitable,” explore some of the work that Mormon women are doing in their careers and communities to protect the environment. Finally, Sherrie Gavin’s “On Nature, Sneezing, and Dad,” gives a different perspective, as she reflects on a lifetime of struggling with nature and how those experiences are wrapped up in her most important relationships.

The great environmentalist and author Terry Tempest Williams writes, “If the desert is holy, it is because it is a forgotten place that allows us to remember the sacred. Perhaps that is why every pilgrimage to the desert is a pilgrimage to self. There is no place to hide, and so we are found.” My own humid, woodsy surroundings are nothing like a desert, but this issue of Exponent II makes me believe that Williams’ sentiment can be expanded to other environments. Being in the wild, considering our relationship to it, examining the divine through it, and learning from other women who have spent time there—all of this strips away the places that we go to hide, and allows us to be found.