As the days grow colder, I find myself thinking of my ancestors. Recently my father told me the story of one of our pioneer ancestors, a Danish farmer who came to Utah to build Zion with the saints. For a farmer, he was incredibly cultured. He was a gifted violinist and musician. Like many early saints, he sold most of his possessions to come to America, including his treasured violin.

When he got to Utah, it was nothing like Denmark. Where Denmark was lush and temperate, Utah was arid, scrubby, and desolate. According to the story, when he and his family arrived at their assigned plot of land, he sat down on the bare earth and wept.

After that first day, he picked himself up and got to work. It wasn’t long before he’d built a small cabin for his young family. He didn’t cry again, not after that first day. Instead, he coaxed crops from the land and built a life for himself and his children. And yet, sadly, he never touched a violin ever again. Not even to play a song on a friend’s fiddle. He simply gave it up for the rest of his life.

I don’t know what to make of this story. It breaks my heart to think of the suffering my ancestors endured in cutting ties with their old lives. They gave up so much to live as Mormons in a strange land. Were they happier? Were they grateful? What am I doing to honor their legacy?

More than anything, stories like this cause me to reflect on my own experience with Mormonism. Mostly, I remember all the good that came from my Mormon upbringing. One of my best memories is my own baptism.

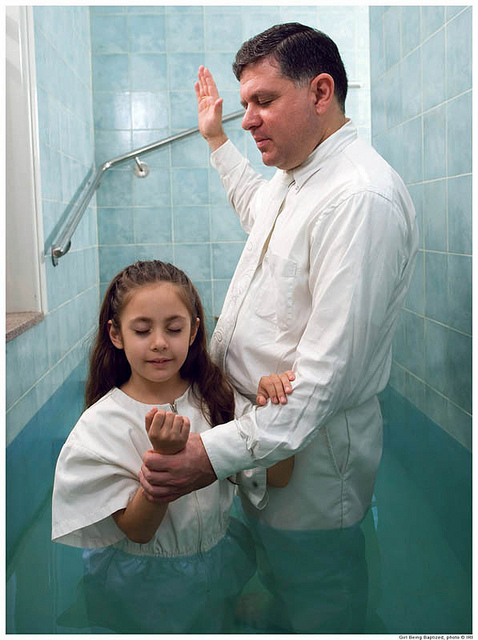

A few days before the ceremony, I stood foot-to-foot with my father in my grandparent’s basement, practicing. He had one arm around my back, the other supporting my hands. He showed me how he would dip me under the water, how I could plug my nose with my free hand, how I would bend my legs to go all the way under.

The day of my baptism my mother took a hundred pictures of me and my father in the church foyer, dressed head to toe in our whites. In the pictures, I smile a toothless grin, my eyes squinting behind giant coke-bottle glasses, my curly hair frizzing its way out of my tidy ponytails.

I still remember stepping into the baptismal font, easing into the warm water where my dad waited for me. My dress ballooned, pillowing around my elbows like a cloud. I remember people crowding around outside the font, their faces a happy blur. I remember my sisters and cousins pressing their smudgy fingers and noses to the glass, how I could hardly recognize them with my glasses off. They were like a swab of paint, a blot of pure, deep love smeared across my vision.

My dad held me in his treelike arms, gently dipping me under the water, just like we practiced. He caught me as my tiny body tried to parachute upwards in my billowy white dress. When I was back on my feet, wiping the water from my eyes, my dad wrapped his arms around me and kissed me on the top of my head, like he always does.

My mother met me in the bathroom with my glasses and a thick fuzzy towel. Even after climbing the steps in my cold, dripping dress I felt warm and held. My mother undid my braids and put bow barrettes in my hair. When we got back to the congregation, my grandma, who gave a talk, gifted me an antique key that she’d kept on her nightstand for as long as I could remember.

“Being baptized is like getting a key straight to heaven,” she said, placing the key on a string and tying it around my neck. I wore that key for nearly three years, almost never taking it off, not even to sleep. I don’t remember much else from that day, except that every part of me felt warm and glowing and golden.

Now that I’m grown, I long to give my children access to spiritual milestones like these. They make up the beautiful, beating heart of our religion, and I want desperately for my children to speak that same spiritual language. And yet, despite such potent memories, I find it difficult to square the Mormonism of my past with the Mormonism of my present.

For one thing, I’ve come to realize that my experience with Mormonism was one of immense privilege. I wasn’t black. I wasn’t gay. My home life was stable, predictable, and nurturing.

It wasn’t until much later that I realized that this wasn’t everyone’s experience. I was exposed to stories of people who had been deeply traumatized by Mormon culture and doctrine. Some had even been physically hurt or abused by people in positions of power. Hearing these stories, I began to realize that some aspects of Mormonism have actually caused me deep pain as well. I had (and still have) deep shame about my body. In my youth, I constantly felt that I was not worthy enough, pure enough, or pro-active enough in my gospel dutires. I also internalized the idea that I was supposed to endlessly sacrifice in order to live the gospel—that my own boundaries and desires didn’t matter. Since then, I’ve also had ugly encounters with leaders in church, and have faced both rejection and censure from people who were supposed to be guardians of my spiritual growth.

And so, as I’ve grown older, my relationship to Mormonism has evolved. In many ways, it’s grown to be more expansive, more inclusive, more transparent than it ever was in my youth. In other ways, it’s grown more obtuse, less articulated, and less concrete. This is one reason I feel so heartsick when I think of the pain that Mormonism has brought into my life and into the lives of my loved ones. Because for all its bitter flaws and tangles, Mormonism still feels like home.

And as for my current family, we still haven’t discovered what our spiritual heritage will look like. My hope is that it’s both the same and different than the Mormonism I grew up with. Right now, it’s mostly described by all that I hope for. Not only for me, but for all of us with deep ties to Mormonism.

For one, I hope that we’ll find safe corners, that we’ll build circles of love and protection where we can be vulnerable and loving and true. I hope that we’ll be like our pioneer ancestors, that we’ll turn our backs on the ugliness of our past, not to forget, but to forsake and heal. I hope that we can pass on our religious traditions in a way that’s both meaningful and respectful to those who have suffered inside the church. I hope that we can welcome those who are vulnerable into our circles, to hold space for them and grieve with them when they need us.

But most of all, I hope that the future feels bright and full of promise, like me at eight years old—a golden girl dressed in white, standing barefoot in a pool of blue, encircled by all that’s bright and beautiful.

3 Responses

Thank you for your hopeful outlook!

Becca, this post is beautiful and so touching to me. Thanks.

This is beautiful! I feel like I am in the same spot. With two small children, my husband and I don’t know what our religious future will look like- for us or them. Mormonism will always be apart of who we are, but how will it look? There are so few unorthodox Mormon examples. Its hard to live in the gray when the church teaches a very black or white doctrine.