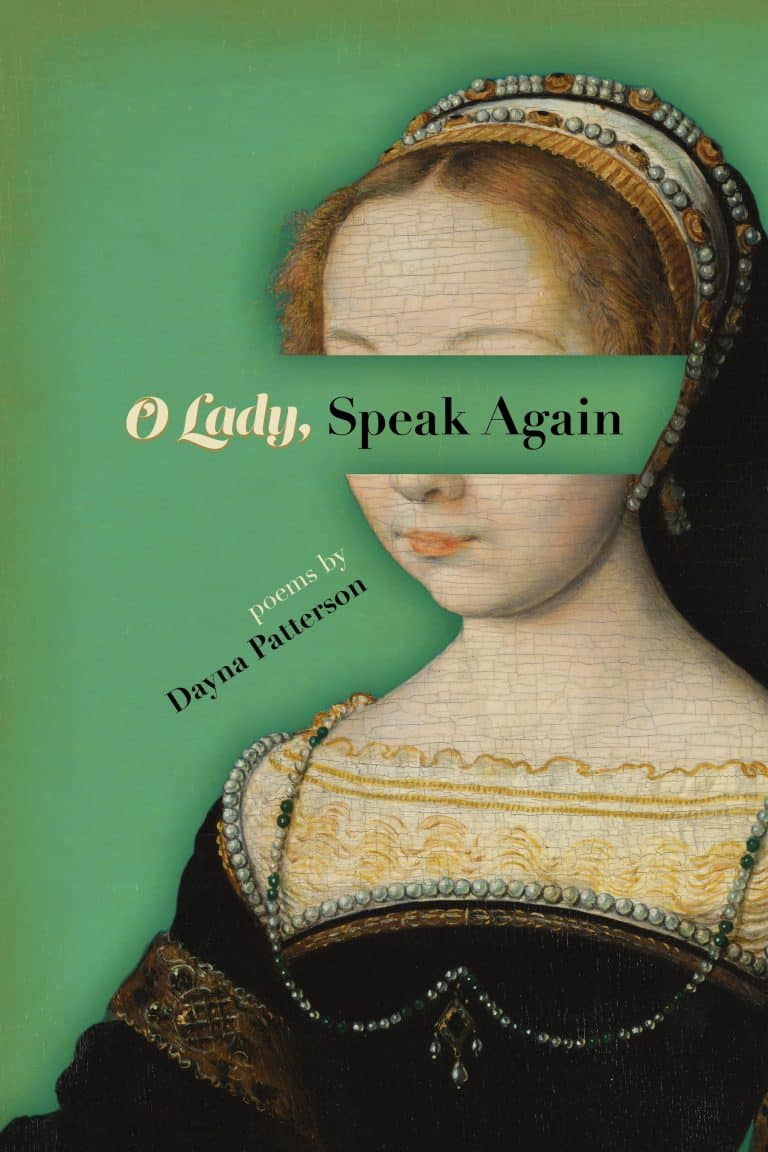

Illustrious poet and former Exponent II Poetry Editor Dayna Patterson has done it again. Her new poetry collection, O Lady, Speak Again (Signature Books, 2023), is everything it promises to be and more — a witchy, spell-soaked collection exploring female characters from Shakespeare’s plays with a refreshing, feminist twist. The poems grapple with women’s roles in Shakespeare and also in Mormon culture.

The poems grapple with women’s roles in Shakespeare and also in Mormon culture.

I’m an unabashed Patterson fan and have been since I first encountered her chapbook Titania in Yellow, which O Lady, Speak Again includes and expands upon. My first experience reading Patterson demanded reading the poems aloud for the sheer fun of it — she is an ingenious wordsmith, with a poem in this volume called “How to Give Birth to Words” (93). When I finished reading that first chapbook, with mouth-drop awe and a “do it again” impulse that prompted me to start rereading immediately after finishing the book, I knew I would never again miss anything Patterson ever wrote.

O Lady, Speak Again had the exact, delightful effect on me. It’s vivid and whimsical, cutting yet delicious. This volume is for a literary general audience (Patterson has an impressive resumé and publishing records for her poems) — but it is also a feat and triumph for our community. Patterson places Shakespeare alongside quotes by church leaders, her own family members, and heralded writers such as Carol Lynn Pearson, Terry Tempest Williams, Rebekah Orton, Suzanne Elizabeth Howe, and others. It’s a party with many of the coolest people, real and fictional, in attendance.

I’m especially struck by Patterson’s compelling, revisionist lens. In “And Why Not Change the Story?” the speaker calls out Shakespeare as being a revisionist himself, changing his source material — such as changing Juliet’s age unnecessarily from 16 to 13, “just shy of a sonnet” (13). In another poem centering Juliet, she writes: “I want to rage at your ‘creator’ — dear puppet, let’s be honest, he’s pulled your strings along … O, Patriarchy. For my daughter’s sake, for every girl’s sake, I want to cut these strings” (73).

“In this Version” invites us to imagine Ophelia going to a women’s college to study botany (8). Later in the collection, we go even further with this resurrection, with Ophelia renaming herself “Lia — bearer of news, of good nows,” who is allowed to grow old (73). Patterson gives us new glimpses and beautiful renderings of Miranda, Cordelia, Jessica, Hermione, Perdita, Viola, Lady Macbeth, Titania, Paulina, and even Juliet’s Nurse. Through this volume, Patterson bids these women — and all women — to speak up, to speak again. “Our hands stained with / yes.” (104). It feels like an invitation as well as an invocation. She calls us into the “O” of tragedy, to examine the faith of our fathers, to listen hard to the experiences of polygamy, and to also feel the power of female relationships and the “wildflowers wicking” our ankles (72).

This collection is personal and urgent, with many “self-portraits” and deep investigations of past and selfhood. Here, the speaker journeys from her days as a devout Mormon girl, “the sin of sex distant as Saturn with its chastity belt” (17), to a missionary offering up celibacy as a solution to queer couples as if to say “cut without spilling blood” (35), until the speaker is then a softened woman who peels “away old faith like sunburnt skin” (36).

Patterson dedicates this book to “fire-speakers” in her life. She herself is a fire-speaker of truth, a voice that wakes me up and puts a skip in my step. These poems are feminist magic — playful, yet powerful and poignant — and I am left spellbound.