When Exponent canceled its retreat in 2020 and again in 2021, any relief I felt in not having to deliver a keynote address was overwhelmed by a desire to celebrate the importance of past retreats in my life. This essay is a small gesture in that direction. It builds on a kind of dialogue between the things I remember and the things I have been able to document in my patchy journals. As a historian, I know better than to trust anyone’s memories, including my own. Human brains have a way of shifting things around in random ways. Written records are stickier. In a pinch, they may even help settle an argument. So, my first take-away point from this essay is simple: don’t throw away anything that even pretends to be a journal. The second may at first seem contradictory: cherish your memories. For all their deficiencies, memories often tell us what we care about.

Although I am known for my work on early women’s diaries, I have never thought of myself as a diarist. The small stack of journals I consulted while writing this essay has forced me to reassess that assumption. On top of the stack is a little chronicle I began on July 11, 1953, my fifteenth birthday. Although I managed to keep it going for only nine months, it provides irrefutable evidence that even as a kid I loved Girl’s Camp. It also tells me that early on I was determined to become a writer. My second journal, marked “Record” in gold on the cover, contains only eleven entries between 1961 and 1963. Yet one of these records is my encounter with Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique. “How wonderful in the midst of diapers & dishes — to know that I can be a woman and have brains, too,” I wrote. I added nothing else in that diary for the next 13 years.

I opened it again in 1976. By then, I had five children, ranging in age from sixteen to one. After six years of part-time study at the university where my husband was a professor, I had begun the dissertation that years later would become my first book. Although my life had never been busier, something impelled me to keep adding entries to my once abandoned diary. When I had filled its pages, I switched to cheap composition books, completing five of them by July 1999. I did not write every day. Sometimes I went months without recording anything, and in the last book I wrote on only one side of each page. Without really intending to do so, I created a more than two-decade-long record of significant events in my own life and those of my children. I also captured small moments in the complex history of Exponent II.

If I had written this essay without consulting my diaries, I would have said without hesitation that Exponent’s retreats began on or before 1974. I knew that in the way women often know things: because I connected it with a major transition in my life, the birth of my last child. I believed I became pregnant with Amy shortly after an Exponent retreat held at my house. Since she was born on August 8, 1975, that retreat had to have been held toward the end of 1974. But because my diary entries didn’t pick up until 1976, I had no way of confirming that. That was a problem because the retreat mentioned on Nancy Dredge’s impressive Exponent timeline was at Hillsborough, New Hampshire in 1983.

I consulted several of Exponent’s “founding mothers,” hoping someone would be able to confirm my memory. None of them had the slightest interest in my obsession with chronology. Although two of them agreed that we held retreats before 1983, they insisted that these were “only for the Board.” I didn’t much like that answer because I knew that from the pink Dialogue onward, our group had always prided itself on welcoming anybody who wanted to come to our meetings, even if by doing so we risked having people spread tales about our supposed feminist heresies.

After several days of fussing over this seemingly inconsequential problem, it finally occurred to me to consult our beloved little newspaper. Since I had already given my old issues of Exponent II to the Schlesinger Library, I had no choice but to use the awkward digital edition provided by BYU through Internet Archive. (Many thanks to whoever linked them to the Exponent II website.) When a word search failed, I decided to skim the earliest issues from the beginning. To my astonishment, the headline “Retreat” popped out on page 1 of Volume 1, Issue 1, dated July 1974. That article contained a report of an October 1973 retreat held somewhere west of Boston where the idea for starting the newspaper had begun! Eleven women and several babies had been in attendance.

It took less than five minutes to reach Exponent II’s third issue. There on the second page of the December 1974 issue was confirmation that “thirty women from Massachusetts and New Hampshire” had recently spent two days “in retreat” in Durham, New Hampshire, at the home of Laurel Ulrich. I was impressed that the number had jumped from eleven to thirty in just one year. The writer explained that there had been delightful meals, jogs in the woods, open discussions, and formal presentations on a variety of topics, including “for some of us,” a discussion of progress, problems, solutions, goals, and dreams related to the production of Exponent II. In short, this was the sort of retreat that hundreds of women have since experienced, a gathering sponsored by Exponent that included both those deeply involved in producing the paper and anybody else who wanted to come. According to the author, the participants came away with a greater understanding of themselves and each other. “The hours were full,” she concluded. So, I hasten to add, was my unfinished house.

I don’t know why it took me so long to consult the paper. I knew in my bones that our gatherings had produced our projects, rather than vice versa. Everything our little group had accomplished since 1969 had begun with open talk, gabfests like the one I documented in my diary on January 7, 1979. Held in Judy Dushku’s living room, it had begun as an “Emmeline Press Meeting,” then devolved into a late-night sharing of “disillusionments & testimonies” produced by a “seeming link between politics & pronouncement from Salt Lake.” One participant asked, “How can the Church do this to my testimony?” But true to form, we felt better after talking it through.

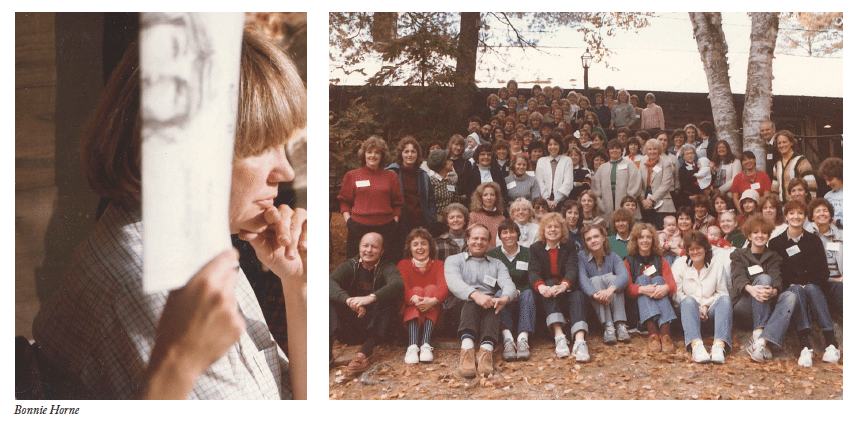

I do not know when and how informal gatherings such as this one led to retreats. I suspect Carrel Sheldon, who had some experience with then-popular self-realization groups, may have suggested the form. Some of the retreats I mention in my diary occurred in people’s homes or vacation houses, others in what were probably rented spaces. People who were involved in the paper invited friends to join them in the same way we invited others to a church event. In May 1982, I took a friend from my ward in New Hampshire to a retreat held in Framingham, Massachusetts. In my diary, I noted the presence of “a large group of single women & many young mothers.” I explained that because Judy, Carrel, and a couple of others I had expected to see were not there, Bonnie Horne and I attempted to fill the gap. I wrote that we “felt very maternal.”

For me, the biggest surprise in my diary accounts was how integrated these early retreats were with my activities in my own Latter- day Saint congregation. In fact, the earliest full description of a retreat in my diaries is the one for October 8, 1978, organized by the Portsmouth Ward Relief Society. I noted, “Much anguish & dissatisfaction expressed. But also — much sisterhood & sharing & a generally ‘I can cope now’ feeling by morning.” That sounds a lot like an Exponent retreat to me. I had obviously been free in sharing my enthusiasm for such events with local Relief Society leaders. One of my favorite diary entries records attending two retreats back- to-back: “I left the Portsmouth Ward women’s retreat at 7:30 a.m. after staying up most of the night & drove to Harvard, Mass for the Exponent retreat. What a feast of contrasting & harmonizing colors, tastes, sounds, & feelings!” Yes, these events were both contrasting and the same. When given time and an atmosphere of support and openness, women talk. When we feel understood and supported, we talk more and become stronger.

My diary entry for March 7, 1981, was filled with family news. It mentioned that I had sent the revised draft of Good Wives to my publisher. In the midst of the jumble, I added: “The Exponent retreat here circa February 6 was marvelous. See Nancy’s editorial in the paper.” That editorial appeared in the Winter 1981 issue under the title “Retreat and Rejuvenate.” It explained that because recent retreats had become a bit haphazard, the organizers had been more ambitious in planning this one. I think anyone who has ever attended an Exponent retreat would recognize its description, including its emphasis on food. Nancy reported that Exponent’s “in-house gourmet chef,” Linda Othote, had brought all the ingredients for a fabulous but simple menu and organized us into crews to put each meal together. I still have recipes from that retreat. My husband, who had decamped to Boston with our children, returned home just in time to see departing retreaters stuck in a snowbank. Although I can’t prove that it actually happened, I have a vivid picture in my mind of Mimmu Sloan single-handedly lifting a bumper out of a rut.

Histories of Mormon feminism often refer to us as “the Boston group.” In fact, few of us lived in Boston proper. Our home area, which extended from New Hampshire to Rhode Island, was one node in the creation of what Leonard Arrington called Mormonism’s “unsponsored sector.” From the beginning, we were connected with writers, editors, subscribers, and readers from similar nodes in Washington, D.C., Chicago, Denver, Provo, Salt Lake City, Berkeley, and beyond. My diary records a surprising number of in-person as well as virtual encounters with like-minded women based in such places.

In May 1982, some of us participated in the “Nauvoo Pilgrimage,” an event organized by women historians who had been meeting together in Salt Lake City to discuss their research on early Latter- day Saint sisters. As a way of honoring the 140th Anniversary of the founding of the Nauvoo Relief Society, they welcomed 53 women to a three-day event in Nauvoo. For those of us who had grown up with idealized portrayals of our pioneer foremothers, the presentations by Carol Cornwall, Maureen Ursenbach Beecher, Linda Newell, Jill Derr, and Lavinia Fielding Anderson were transformative. I love the snapshots somebody took of us hamming it up in a Nauvoo sculpture garden. We both embraced and pushed back against the sanitized legends that had shaped our lives. For most of us, the highlight of “Pilgrimage” was the so-called Quaker Meeting on the final morning, where the poets and the non-poets among us tried to capture the spiritual meaning of what we had learned.

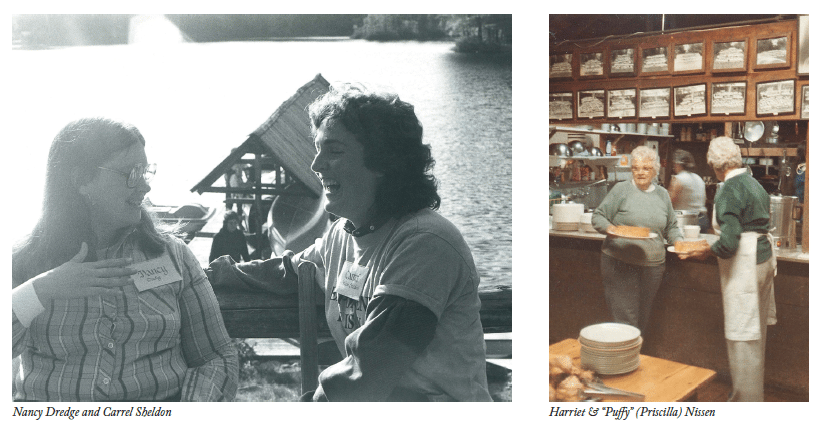

Pilgrimage helped inspire Exponent’s first truly national retreat, a three-day event held in October 1982. We called it the “Exponent Reunion,” perhaps because we hoped to see the return of women who had worked with us over the years and then moved away or who were connected to us and each other only through the paper. Sue Booth- Forbes spent much of the summer looking for just the right setting. She found a circa 1922 camp in Hillsborough, New Hampshire, run by two amazing sisters, Harriet & “Puffy” (Priscilla) Nissen. As I wrote in my diary, Hillsboro Camp had “a pond, beautiful woods, surrounding fields with bell-ringing cows, and log cabins with names like Sing-Sing, Bug House & Doggy House, and with genuine five- hole outhouses.” For me, the outhouses brought back memories of being at my grandfather’s cabin in Big Springs, Idaho, where an acre of bubbling springs produced a fork of the Snake River. Our New Hampshire site was not quite that magical but it was impressive.

The home-cooked meals were among its charms. Harriet and Puffy and their helpers served homemade bread and rolls, jams from local berries, salads filled with fresh vegetables including sweet-tasting summer squash from nearby farms, and eggs and meat from chickens that had been fed from our dinner scraps. According to my diary, 100- 120 persons attended. Other accounts reveal the presence of six or seven somewhat dazed men. When I read my own description, I was stunned to realize that this was also the retreat where novelist Virginia Sorenson and her cousin, labor activist and consumer advocate Esther Peterson, spoke. In memory, I saw us introducing them to a space that we already loved and had made our own. No. We met both our new site and members of Mormonism’s so-called “lost generation” at the same event. In my diary, I described our guests as “two lovely ‘ex-patriots’ who nevertheless reflect Mormon ways.” Although both left Utah and apparently the Church in young adulthood, they both carried much of their Mormon heritage with them.

I knew Virginia Sorenson’s novels quite well because the essay I contributed to Mormon Sisters had explored fictional portrayals of pioneer women, a genre in which she excelled. I was thrilled to meet her and listened intently to her description of her struggle to find herself as a writer. She was not only eloquent but had a self-deprecating sense of humor. She quipped that she had been married twice “with a little overlap in between.” I have a more vivid memory of Esther Peterson. I believe we were all together in the big room with the twiggy sign over the fireplace that read “May the fires of everlasting friendship burn.” People were sharing their woes when Esther gently raised her hand and said something like, “But wouldn’t it help to look beyond ourselves?” She asked if we remembered a Sunday School song that she then began to sing: “Have I done any good in the world today? Have I helped anyone in need? Have I cheered up the said, or made someone feel glad? If not I have failed indeed.”

It was a surprising moment, the outside radical, the labor organizer, and “Great Society” appointee telling us to remember the lessons we had learned in Sunday School. I don’t think I made up the moment toward the end of the Reunion when I heard Esther express her appreciation for having been invited and then said, “Perhaps if we had had something like this when we were younger, we would have stayed.” I wanted to believe that was true.

I attended many more Exponent retreats after that. I wrote about some but not all of them in my diary. On July 22, 1996, I copied a scripture I had discovered at the latest one. It was from the Sermon on the Mount, Luke 6:38: “Give and it shall be given unto you; good measure, pressed down, and shaken together, and running over.” Obviously something interrupted me, and I didn’t complete that entry until a month later, when I wrote, “I feel like my life has indeed been pressed down — compressed into high-density land — and still runs over! Is this fullness? Or a kind of excess — an overabundance that leaves one frantically trying to grab more [?].” With some irony, I added, “A drop can be delicious.” By the time I made that entry, my children were grown; I had won a number of prizes for my historical work, and I had just joined the history faculty at Harvard University. Although I loved the work I was doing, I was daunted by the unexpected attention I was receiving. Over the next twenty-five years, Exponent’s retreats helped keep me sane. I look forward to the next one. ⋑

Laurel Thatcher Ulrich is a retired professor living with her husband in Bala Cynwyd, PA.